Marcia Bjornerud says she goes around listening to the stones. They may not tell you anything, but they tell her things like in the past, palm trees shaded a sweltering Arctic; that the summit of Everest is full of fragments of ancient aquatic creatures; and that right now, the ground beneath our feet moves, folds, sinks, rises, and cracks.

Geology, Marcia says, has a reputation for being "boring" because it involves "all the tedious work of paleontology, but without the velociraptors." Its success usually lies in finding rare earths, fossil fuels, or even an earthquake. But one day, this Geology Ph.D. from the University of Lawrence in Wisconsin decided to address this great rock we call planet Earth and ask it the great question of human history. Who are we? "We are earthlings. I know it sounds like science fiction, but I think it is important to reclaim the term. In English, it is said 'earthling.' The ending 'ling' denotes something small. That is, we are here, but we are not in charge."

Since Earth is almost 5 billion years old, and has only hosted human beings for 0.007% of its life, it is evident that humans are not the ones in charge of this ball traveling through the universe at 107,000 kilometers per hour. "Thinking of Earth as an inert and indolent piece of rock is dangerous. It is not a silly matter that we can deceive and exploit. This view has led us to an environmental catastrophe, but also to cultural alienation: we no longer remember who we are."

Marcia Bjornerud, in addition to being an expert in earthquakes, has been a daughter, sister, friend, wife, mother, teacher, and widow. She recounts this in Listening to the Stones. Exploring the Wisdom of Rocks, just published in Spain by Editorial Crítica, where she uses them to carve out unusual memories. "Thinking like a geologist is contemplating time scales that astonish the imagination and reveal the planetary forces behind our earthly existence. On a deep psychological level, we need to feel our place in its history."

Head to the mountains and pick up any stone, but instead of kicking it or throwing it away, consider this reasoning. It may have been abandoned by New Zealand when the last supercontinent split. Or it may have been deposited by a river that has not flowed in ninety million years. It may have been expelled from the Earth's mantle during a volcanic eruption. That one day it was part of a desert, or an ocean. "Time," says Bjornerud, "is one thing for human beings, but radically different for the planet we live on. Rocks can open our minds to an unexpected and enlightening experience: an awareness of time."

-But ours, compared to theirs, is quite depressing.-We all fear our mortality, but rocks reaffirm to us that the past is no less real than the present. There is a certain existential comfort in being able to understand the Earth and where we come from. There is a quote I heard from the Polish rabbi Simja Bunim, who said that you should always carry two papers in your pockets. In the left one should say: 'I am ashes and dust.' And in the right one: 'The world was made for me.' Both are true. We are ephemeral, we are temporary, we are short-lived organisms, but we are here. The world is now for us, as it was for other generations of humans and earthlings before humans. When I delve into this existential well, I find some comfort. We need to think more about the future. Geology is not just about the past.

The rocks around us, says Bjornerud, tell us that change sometimes occurs through violence, but mostly through patience; that survival involves the ability to resist, and the wisdom to recognize that the world can change in a single day. One of the many miracles of the human mind is that it can represent radically different scales of existence than its own: the inside of an atom, the far side of the Moon, the Pillars of Creation, the Paleozoic era. However, "in the West, especially in the United States," points out the American geologist, "there is the idea that we simply burn the past and keep moving towards something: 'I'm not sure where we're heading, but the past is gone.' And for me, rocks are a reminder that everything is made of time and that this time continues with us. And it is comforting that there is a kind of continuity. It is a very important part of our lives, and it would be terrifying if everything were erased. Most modern humans live in a narcissistic present, thinking it is the only moment that matters. And that is one of the reasons why so many people have mental health problems, because they do not understand their place in time."

Earth's crust, the geologists' textbook, represents less than 2% of the planet, and much of it is invisible: hidden by vegetation, submerged under oceans, buried under layers of rock that are not the rocks you are looking for. Everything below the crust, beyond Jules Verne's imagination, is inaccessible. The deepest hole humanity has managed to dig is the Kola Superdeep Borehole, a project of the USSR during the Cold War: approximately 0.2% of the way to the Earth's center. "We have to start thinking like a planet," says Bjornerud.

-And how do we do that?-For life, it is not just that this planet had the right initial ingredients and was at the correct distance from the Sun. Earth formed from the same primary materials as its siblings, but ours has recombined those ingredients to turn them into rocks that are not found anywhere else in the solar system, and then has invented processes that continuously recycle and regenerate them. Plate tectonics is a planetary-scale respiratory system that makes our planet habitable. Thinking like a planet means operating in a way that allows for relative long-term stability.

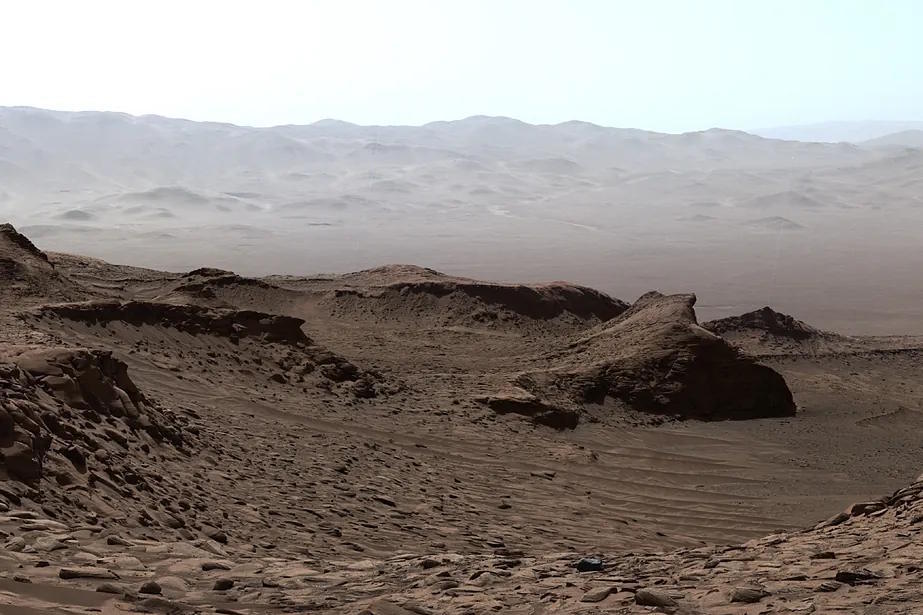

Other planets do not think that way. Mars has a single rigid planetary-sized plate that does not move relative to its mantle. We do not know if there will be life on other planets, but what is certain is that there will be many rocks, so it is most logical to think of a loving God of geology. "The oceanic crust is recycled, water is recycled, carbon too. That is the key to thinking like a living planet: this habit of recycling and recycling on many different scales, both spatial and temporal. Earth is an incredibly sophisticated system of systems that, in some way, has invented itself. And we geologists have not been very good at conveying the extraordinary nature of that. You know that here in the US there are people who believe we could colonize Mars."

-Ah, we can't?-Well, I think we could land there and explore. But colonizing it and turning it into something like Earth is irrelevant and dangerous. The worst day on Earth will be much better than anything on Mars. And this is due to a lack of understanding and respect for Earth's long-term habits. They cannot be designed to exist. They are a product of evolution. Earth is full of mobile components, many of which we do not even understand. Microbes perform most of the geochemical cycle, and we do not even know which ones are present, let alone to suddenly export them, or in a couple of human generations, to another planet. It takes my breath away. It is so arrogant.-But we have to think of something, because we will not have this planet forever.-Well, I trust this planet. It is very old and resilient. It has been here for 4.5 billion years, and modern humans have only been here for a few hundred thousand. We evolved here, we have deep roots here, and our bodies are well adapted to this place.-But the Sun will one day go out.-But in a very distant future. I am more concerned about the next hundred years than about what will happen in 5 billion years.

"Earth is an incredibly sophisticated system of systems that, in some way, has invented itself"

In her stony biography, Marcia Bjornerud recounts that geology was a field dominated by men.

She faced reality head-on when, upon arriving at her new job, a highly esteemed emeritus professor welcomed her into his office and asked her to sit on his lap. When dealing with relationship problems and needing to take geological distance, she discovered that geographical cures are rarely effective.

Geology does not believe in the magical or healing properties of rocks: "I suppose I am a bit skeptical in a very literal sense, because after all, we are all made of stones and water." But Marcia Bjornerud does believe in the magical or healing properties of tectonic plates: "I believe that certain places have power, especially where the dynamic forces of the Earth are evident, like Iceland. There you feel the Earth's beating heart because it comes close to the surface. It is undeniable that there is something alive just beneath our feet. Earthquakes are a visceral reminder. It is a transcendent and terrifying moment to feel so physically overwhelmed by the Earth in an instant. But they don't have to be dramatic places. They can be quite peaceful, where human presence is minimal."

If the beginning of the 20th century was the takeoff of physics, Bjornerud believes that the beginning of the 21st will be that of geology, where she does not believe we will travel to the center of the Earth, but rather to its immediate surface.

The great achievement will be to discover, she points out, that soil microbes, ocean microbes, even rocks, govern the world's chemistry. "We haven't even begun to take a census. We know that there are rocks on Earth created mainly by life, by microorganisms. That is one of the reasons why Earth has so many different types of rocks, because life forms participate in the cycle." -"And from there to immortality: Dust you are and to dust you shall return. -That's right. We are part of these cycles. This is what makes Earth habitable. Everything is reused, readapted. The calcium and phosphorus in our bones will last for some time and then decompose. Of course, it depends on the details of our burial. But yes, everything will eventually be recycled, not in the human sense, but through physical and chemical decomposition. Some of us may become fossils. Perhaps we will be discovered by archaeologists. The assertion that Earth is a living being was once considered an exaggeration, but today we know that almost half of minerals are biogenic, their formation depends in one way or another on a living species. Most of us will physically become part of this infinite cycle of elements that define Earth."