When all resources have been exhausted, sometimes only the markets are capable of putting everything back in its place. Beyond the exuberant and lively stock markets, the debt market is the true giant of the markets: the one to fear and respect. And Donald Trump knows this very well. But why is it so important? Could it really unleash a financially immeasurable tsunami? Everything points to yes. The global debt market (public, from states, and private, from companies) reached 140.7 trillion dollars worldwide in 2024, according to data compiled by SIFMA (Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association). Of this, only 39% corresponds to the U.S. with 55.3 trillion dollars issued, more than double the next most important market, the European Union, which represents 18.4% of the total. This implies that the U.S. has issued in debt bonds more than double the value of its entire economy, whose GDP (Gross Domestic Product) reached nearly 27 trillion euros last year. Or, if you prefer, it's 36 times the size of the Spanish economy. Out of that amount, a minority, 11.2 trillion, corresponds to debt issued by its companies.

Stock market capitalization, despite grabbing all the headlines, represents 82% of the size of the debt market, with 115 trillion dollars.

With the backdrop of the trade war, the debate over the excessive U.S. deficit is back on the table, a country - let's not forget - that has the ability to print money if necessary, hence it can incur debt without major issues. Its figures would be unimaginable for any EU country. More than enough to buy a one-way ticket and a long stay for the famous men in black who roamed southern Europe during the debt crisis of 2012 and subsequent years.

What is the magnitude of the problem that Donald Trump wants to reverse? Basically, the U.S., the country that patented the fiercest capitalism, does not control its debt, which last year reached 35.46 trillion dollars. All-time highs. In the last 20 years, it has tripled, according to U.S. Treasury data. These figures represent 123% of its GDP, with a deficit of 1.83 trillion dollars, close to 7%. Something that would be unthinkable in any EU country.

What does the market fear? That the stampede of investors will cause an increase in the financing costs of the U.S. government, which currently average 3.32%, according to data from the American Treasury. Also at decade highs.

One reasonable fear is that a possible recession in the U.S. economy - as expected, following the trade war initiated by Republican Trump - could lead to increased debt interest expenses due to higher financing costs. According to Barclays, every reduction between 0.5% and 1% in GDP growth could increase bond yields by 0.3 to 0.35%. Good for investors, bad for the public finances that Trump is trying to redirect.

In recent weeks, China has been accused of being behind the fall of U.S. bonds; of investors fleeing from the T-Note. It was said that they were selling massively. Beijing neither confirms nor denies - as is customary - but it would be unfair to blame the Chinese regime for something that has been happening for years. At least, in the last two years, China has been a net seller of U.S. debt, meaning they sell more than they buy. Japan was also in this situation in 2024.

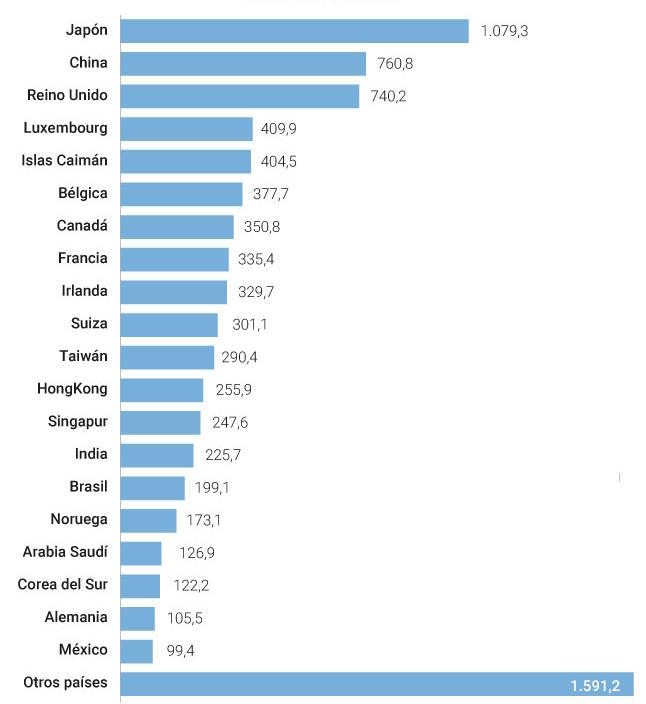

This leads us to the next question: Who holds U.S. debt? Foreign investors hold 26% of the total long-term debt; 20% of Treasury Bills and up to 33% if we focus only on public bonds (7.3 trillion dollars), according to data compiled by Barclays. In the last two years, foreign investors have been the largest buyers of U.S. debt, approximately a trillion dollars each year, according to data from the British bank, with half in U.S. Treasury bonds. This is despite China gradually withdrawing. It is, along with Japan, the largest holder of U.S. debt, followed by the UK, Luxembourg, or the Cayman Islands. However, more than half of the debt is held by U.S. investors themselves.

The paradigm shift brought about by Donald Trump focuses precisely on the debt market, despite the fact that it is always the stock markets that grab the headlines. The U.S. bond "has suffered a loss of status, small but sufficient to spark," says Alberto Matellán, chief economist at Mapfre and director of La Financière Responsable. For the first time in the 21st century, American debt has ceased to be a safe haven for investors, with sales that led the T-Note to rally from 3.9% to over 4.5% in the days following Donald Trump's announcement of imposing tariffs. This is how it has worked in major financial crises, such as in 2001 when the dot-com bubble burst; in 2008, the eurozone debt crisis of 2012, or the September 11, 2001, Twin Towers attack.

The same happened with the dollar. In the 12 days following Trump's announcement surrounded by roses, the weakness of the currency was palpable among the major world currencies. It is particularly significant against the Swiss franc, an unparalleled safe haven, which appreciated by almost 7% against the dollar. It also lost ground against the euro, down to 1.13 in the exchange rate (and some see a return to the 1.20 that was present for so long); and against most currencies of major economies. It falls against the Danish krone, the Japanese yen, the Canadian dollar, or the British pound.

Given the mistrust generated by the new U.S. government, investors have sought safety in Germany, the country that has managed to reduce its public debt from 80% to 62% of GDP after the pandemic - quite an achievement - and has therefore allowed itself the luxury of easing its debt limit and approving a national infrastructure and defense plan worth 500 billion euros. The German country, renowned for tightly controlling its debt, finances itself up to 2 percentage points cheaper than the U.S., with a 10-year bond hovering around 2.5%. The last 12-month Treasury bill auction closed at 1.86% - the U.S. pays 4%.

"Right now, the feeling is that European debt is acting as a safe haven. The U.S. faces debt maturities worth 3 trillion dollars this year," says Nacho Zarza, an analyst at Auriga Bonos. "You start with debt maturity problems, this leads to the halt of projects and investments, and ultimately affects market confidence," describing the cycle that the United States would be going through.

In every cloud, there is a silver lining. The increase in U.S. debt yields is being seized by portfolio managers to buy bonds when prices plummeted in early April. It is worth noting that this crisis that has made headlines in recent weeks was already anticipated by major investment funds that have been increasing their liquidity for at least a month in anticipation of what might come and because credit was very expensive. And with that same liquidity, they have gone shopping now.

Trump's tariffs, still to be defined, have indeed differentiated between sectors, causing the most affected debt in the early days to be from "automakers, paper companies, or firms linked to manufacturing" in a first phase "to then punish basically everything," says Eduardo Roque, director of Fixed Income at Bestinver, who explains how the interbank market has been under tension in recent sessions, opening clear opportunities, although the situation is much more relaxed now.

Bestinver, which on average has reduced the liquidity of its portfolios from 16% to 10%, mentions companies like the French Faurecia, a manufacturer of automotive components, whose 2031 bond has gone from offering an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of 5% to 11% in recent days. It also mentions the German paper company Progroup with a debt yield of 5% to 7%; or the joint venture of Virgin Media and Telefónica in the UK that reached 6.5%.