Engaging the brain to do calculations and reading regularly serves as a protective shield against cognitive decline. In other words, the more we exercise our neurons in tasks involving mathematical calculations and text comprehension, the later we will notice the effects of aging.

A team of German and American researchers led by Eric Hanushek from Stanford University (USA) reached this conclusion. They discovered that for most people, cognitive abilities increased until the age of 40 before declining, and this did not happen in those with above-average skill use at work or at home. Meaning, those who had jobs requiring intellectual skills in their daily lives, more common in tertiary sector jobs (office) than in primary sector jobs (agriculture and construction, for example).

The findings were recently published in Science Advances, where the hypothesis was presented that changes in skills perceived with age could be due to differences in skill levels between groups.

According to Guillermo García Ribas, a member of the Spanish Society of Neurology (SEN), this article demonstrates that aging "associated with more slowness and more mental difficulty" does not necessarily have to start in adulthood "in the midst of the crisis of the 40s." "No, it doesn't have to be that way for everyone. If a person is cultivated, reads regularly, and does mental calculations, they don't have to start that decline process."

The neurologist highlights that there are reasons to believe that new neuronal connections are formed as part of maintaining an active capacity. "The message it sends is that what you do slows down aging. And that, I think, is an interesting message," García emphasizes.

Even in the early 20th century, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the father of neuroscience, pointed out the existence of brain plasticity, the brain's ability to change throughout life, and how "man can become the sculptor of his own brain."

An editorial in Scientific Reports last year addressed this dilemma: brain decline versus preservation of abilities, regarding a series of articles on cognitive aging. "Stability against the decline in working memory performance is related to brain maintenance, using task-related measures of neuronal integrity (e.g., prefrontal cortex activity) and broader measures (e.g., hippocampal and ventricular volume)."

How was the research conducted?

To verify Hanushek's team's theory, they analyzed data from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), which measured the linguistic and mathematical competencies of a German population aged between 16 and 65, and reanalyzed a large sample of the cohort 3.5 years later. Participants were also asked how often they engaged in activities such as reading emails or calculating expenses at work or at home.

The researchers determined that the average reading and mathematical abilities increased until the age of 40 before starting to decline. Individuals with above-average skill use frequency in the workplace and at home did not show any decline in skills over time.

In the case of white-collar workers and those with higher education levels with above-average skill use, skill levels steadily increased beyond the age of 40 before stabilizing. The authors also observed that mathematical skills declined more sharply with age in women than in men. "The results suggest that the relationships between age and adult skills deserve policy attention, in line with concerns about the need for lifelong learning," Hanushek stated in a note.

Other clues: the 'collateral' effects of the findings

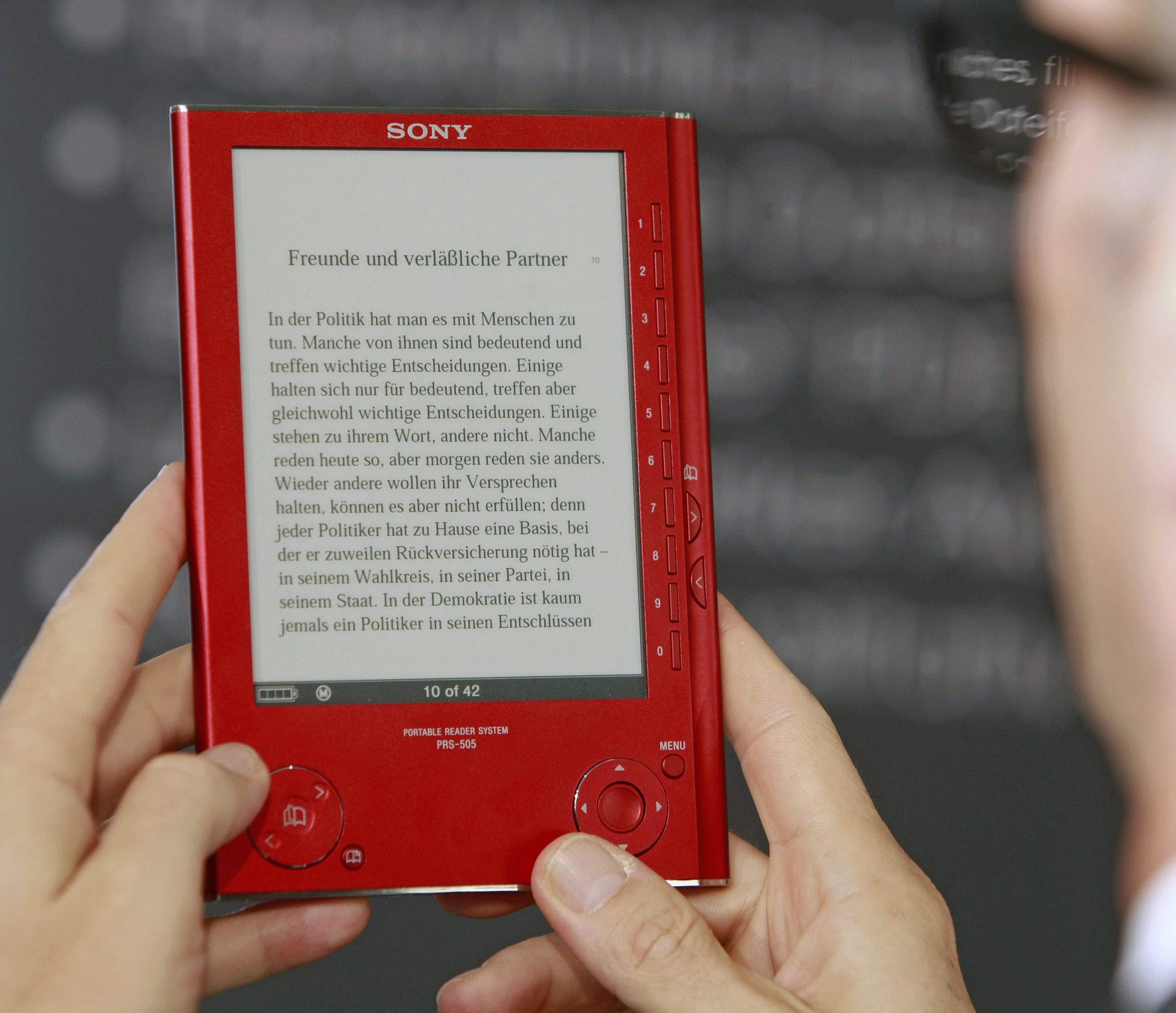

Regarding the power of reading, the neurologist argues about everything that reading entails: "We have always seen that it is a task that goes beyond just sitting. It develops imagination, creativity, one has to get into the plot, understand what is happening." Therefore, García summarizes that this activity "goes far beyond words. And proof of that is that this article also follows that line."

These findings also serve to highlight the protective effect against neurodegenerative disease. "There are patients with the disease, but nevertheless, its impact, its manifestations are cushioned by the brain's previous capacity, by that developed plasticity," García concludes.

This conclusion aligns with the exposition in the editorial of Scientific Reports: "The brain has great potential to compensate for age-related functional and structural changes. Cognitive reserve accumulated throughout life, for example through education and other stimulating activities, can act as a buffer against cognitive decline."