It was discovered on December 27 with a telescope in Chile and immediately became the top concern among asteroids due to the risk of impact in the coming years or decades.

It has been named 2024 YR4 and, according to the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA, it will approach our planet on December 22, 2032, making the surveillance and orbit calculation of this asteroid a top priority for astronomical organizations dedicated to planetary defense.

The current probability of impact on Earth within seven years is currently 1.6%, according to the new calculation made by ESA on Tuesday, which had previously been set at 1.2% on January 29. These estimates align with those made by NASA's Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) and NEODyS, an information system on these rocky bodies.

Its detection has led the UN to activate for the first time the two asteroid response groups - the International Asteroid Warning Network (IAWN) and the Space Mission Planning Advisory Group (SMPAG) - as 2024 YR4 meets the two criteria for their activation: an estimated size larger than 50 meters and a probability of impact greater than 1% at any given time within the next 50 years. Both groups, IAWN and SMPAG, were established about a decade ago, and their warning protocols have been in place since 2018.

The asteroid follows an elongated (eccentric) orbit around the Sun and is now classified at Level 3 on the Torino Impact Hazard Scale (which has 10 levels, with 1 being the lowest risk and 10, a certain collision). ESA has specified that they are monitoring it "actively" and that the probability of impact "is very small."

"The probability of impact with Earth in 2032 is just over 1%, but it is likely much lower, and it should be noted that there is still a lot of uncertainty about the orbit it will follow," explains Javier Licandro, one of the researchers at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands (IAC), in a phone conversation, who is tracking this space rock that will pass within a few thousand kilometers of Earth, much closer than many satellites.

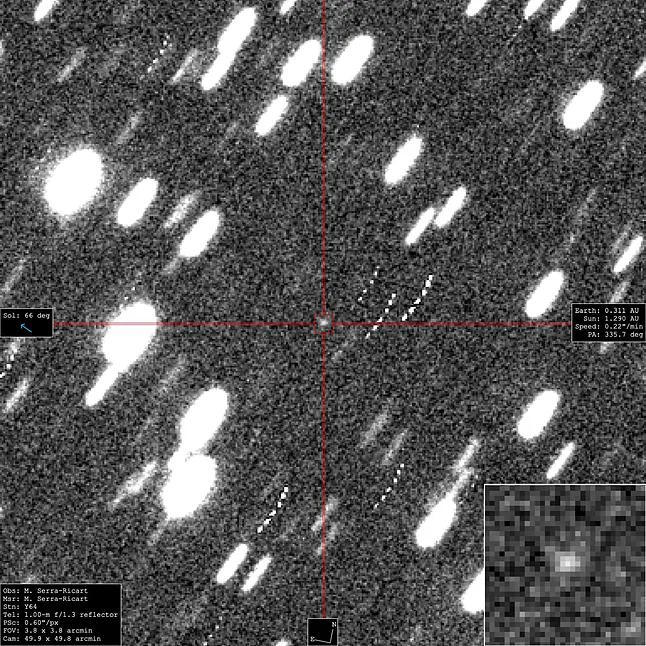

The asteroid was discovered with a telescope located in Río Hurtado (Chile), which is part of the ATLAS network (Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System), to which the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands also belongs. "We have just installed another one of these small telescopes at the Teide Observatory, and soon we will discover new asteroids and comets with it," says Licandro.

The ATLAS network telescope at the Tenerife Observatory of the IACIAC

Since early January, astronomers worldwide have been observing this rock with telescopes dedicated to this purpose to try to calculate as accurately as possible the path it will follow in the coming years. The Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands is studying it with the 10-meter Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC) and the Transient Survey Telescope (TST) of one meter, among others. "Julia de León has taken a spectrum that allows us to know more or less what type of asteroid it is. It is one of the most common in the S-type region, which means it is a rocky asteroid, with slightly processed silicates," says Licandro.

"As we make more observations and refine its position, the probability of impact usually decreases. This often happens because errors and uncertainties in the orbit calculations are also taken into account, and as uncertainties decrease, that factor becomes smaller. This has happened with other asteroids that, when discovered, had a higher probability of impact than they did after more observations," explains Licandro, who points out that another way to view this case is that "there is a 99% chance it will not collide with Earth."

An example of an asteroid that was classified as dangerous with probabilities of colliding with Earth was Apophis, discovered in 2004. However, subsequent observations ruled out an impact in 2029, as well as the potential risk of another approach in 2036.

However, the Spanish astronomer emphasizes the importance of monitoring 2024 YR4: "We have a list that takes into account the impact probability of near-Earth asteroids, and right now it is the object that most concerns us, which does not mean we are terrified, but we are focusing on accurately measuring its position," he states. He admits that, although not typical, as the asteroid is observed more closely, "the probability of impact against Earth could also increase."

ESA, on the other hand, states that we are facing "a close encounter that deserves the attention of astronomers and the public," but also considers it "important to remember that the probability of asteroid impact often increases initially, before quickly dropping to zero after additional observations."

Regarding size, ESA estimates it to be between 40 and 100 meters. "Our calculations indicate that it is much closer to 40 meters than 100 meters," explains Licandro. They have estimated the size from the IAC by measuring its brightness since what they see through the telescopes is a point. "Knowing the distance at which it is, we can estimate its size as it reflects sunlight. The larger the asteroid, the more light it reflects. And this asteroid reflects between 15 and 25% of the light it receives."

The spectrum indicates that this asteroid falls within the range of 40 to 60 meters. "It does not reach 100 meters; if it did, it would be much darker," he affirms. According to ESA, an asteroid between 40 and 100 meters impacts Earth on average every few thousand years and could cause serious damage to a local region.

By way of comparison, the astronomer points out that the object that fell in Tunguska (Siberia) in 1908 was estimated to have a diameter of 50 meters, while the meteorite that unexpectedly impacted Chelyabinsk (Russia) in 2013 - causing over a thousand minor injuries due to the shockwave - measured about 15 meters.

Currently, the asteroid is moving away from Earth in an almost straight line, making it difficult to precisely determine its orbit, according to ESA. In the coming months, it will become less visible until it cannot be seen from ground observatories in April, so ESA will coordinate observations with increasingly powerful telescopes, including the Very Large Telescope (VLT) of the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Chile, to gather as much data as possible in these three months.