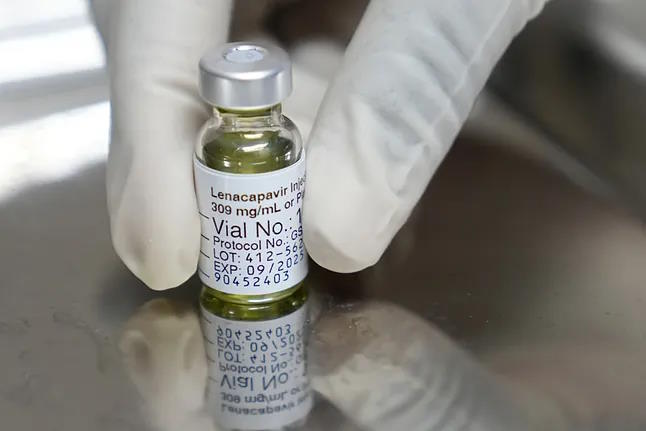

At the beginning of last summer, a trial conducted on 5,000 adolescents and young women in the most HIV-affected areas of Africa showed that a drug injected only twice a year was able to prevent a staggering 100% of infections in the studied sample.

Lenacapavir, the name of the treatment, later demonstrated, as summer was ending, an efficacy that also approached these figures in a different context, among 2,000 individuals of different genders who regularly engaged in sex with men.

These data highlighted the drug's potential, developed by Gilead, to contain the spread of infections when used as pre-exposure prophylaxis in at-risk individuals, known as PrEP, earning it the recognition of discovery of the year by the journal Science.

The journal also emphasizes that the drug has uncovered a target to address HIV that was previously unknown, opening the door to new approaches that could be useful against this and other viruses.

The basic research that led to the treatment, the text points out, provides a new understanding of the structure and function of the HIV capsid, a kind of protective shell that safeguards the virus's genetic information and which lenacapavir targets.

This unique mechanism of action of the drug is precisely what gives it the ability to be effective against infections that have become resistant to other treatments, a use for which it currently has approval.

This is the third time that the journal Science has chosen an AIDS-related discovery as the discovery of the year. In 1996, the development of the first truly effective therapies against the virus took center stage in the recognition. The same happened in 2011 when it was demonstrated that undetectable meant untransmittable.

And in 2024, Science values "the next, although not the last, step in the fight against AIDS, where the rigor of laboratories and the needs of humanity are inseparable," as quoted in the journal's editorial.

"Although the vaccine that could end the pandemic remains elusive, the development of lenacapavir, a long-acting injectable drug that can be taken preventively by individuals at risk of HIV exposure, represents an advance in HIV prevention similar to previous discoveries with antiretrovirals," the text states.

"In my opinion, it is a great advance, especially in prevention, as a means to curb the epidemic," points out Luz Martín Carbonero, a specialist in the HIV unit at La Paz Hospital (Madrid) and a member of GeSIDA, who highlights the drug's excellent results in the mentioned trials conducted in contexts where the virus continues to circulate significantly.

"In the first trial, conducted in women in Africa, zero infections were recorded in a sample of 5,000," the specialist recalls. "Today, in some contexts, it may be the closest thing to a vaccine that we can have."

Currently, the drug is approved to treat individuals resistant to other treatments, but its main potential lies in prevention, especially in contexts where access to conventional PrEP is challenging, there is still a significant stigma surrounding the virus, or there is a large number of at-risk individuals, as noted in the same vein by Ramón Morillo, a specialist in Hospital Pharmacy at Valme Hospital (Seville) and a member of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy (SEFH).

"It can be a very useful drug to prevent infection transmission in vulnerable populations, for example in Africa. It can be effective for prevention since the route of administration and dosing regimen allow the population to access that protection more easily. It facilitates adherence, which allows for sustained protection. And that sustained protection over time can help curb new transmissions and achieve community prevention. It probably won't be the only drug that can help in this goal, but it represents a significant leap," he points out.

Javier Martínez-Picado, principal investigator and ICREA professor at IrsiCaixa, agrees in pointing out that the drug's main potential lies in its role in prevention rather than as a treatment against infection, although he notes that a dosing regimen of two 'shots' a year also poses challenges for achieving sustained adherence.

The researcher highlights the drug's mechanism of action, which inhibits the virus's capsid, a kind of soccer ball-like covering that encases and protects the genetic material. The drug manages to inhibit the virus both at cell entry and exit, giving it a dual mode of action.

In its pages, Science emphasizes that since many other viruses also have capsid proteins, this discovery opens up "the exciting prospect that similar capsid inhibitors could also combat other viral diseases," although Martínez-Picado points out that not all capsids are the same, so specific inhibitors would need to be investigated for each case.

Science also stresses that lenacapavir becoming a key drug to accelerate HIV prevention largely depends on access to the drug.

"The price, which has not yet been set, will determine who can afford it," the document states. Currently, for the approved indication, the drug costs around 20,000 euros in Spain, a figure that doubles in the US.

Last October, Gilead announced the signing of voluntary licensing agreements with six companies for the production and supply of lenacapavir generics in 120 developing countries, although Science points out that this plan does not address the situation in middle-income countries like Brazil, which has the highest HIV figures in all of Latin America, a fact that had already been highlighted by various organizations.