Cancer is a true master of deception, an expert in tricks that uses different stratagems to grow and spread. One of them is relying on the HER2 protein, whose overexpression helps it multiply faster. Up to 4% of all tumors have high levels of HER2, a percentage that rises to 15% in some cancers, such as breast cancer.

This is the target that various treatments are already successfully aiming at, and it is the target of a new CAR-T therapy developed by researchers from the Vall d'Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO) and the Hospital del Mar Research Institute (HMRI).

This approach, which proposes a dual attack against the tumor, has shown promising results in preclinical models, achieving a complete and long-lasting antitumor response in mouse models with tumors derived from patients, as published this Monday in the journal Nature Communications. With this data in hand, the team hopes to start phase I trials as soon as possible to test the therapy on patients.

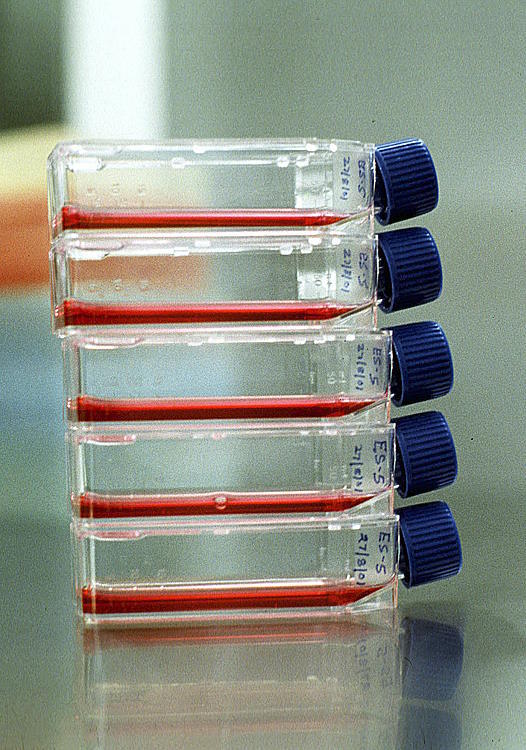

CAR-T therapy is an anti-tumor strategy based on genetically modifying the patient's lymphocytes so that, like hitmen, they can precisely locate and attack only cancer cells.

To make such a therapy work, the first step is to identify a marker that is only present in tumor cells, an antigen that allows clear distinction from the rest.

The Spanish team identified the p95HER2 protein, present in a third of HER2 tumors and associated with more aggressive tumors.

"We developed a CAR-T against that molecule and found it to be effective but not as effective as we had hoped, so we wanted to be more ambitious and continue researching," says Joaquín Arribas, ICREA professor, head of the Growth Factors group at VHIO, director of the Hospital del Mar Research Institute, and lead author of the study.

"CAR-T cells can function as a platform where you can introduce independent therapies. So we decided to add a bispecific antibody that only recognizes very high levels of HER2," continues the specialist, highlighting that this "dual attack did provide the expected effectiveness."

"In our laboratory models, in our mouse models, the mice were cured. Tumors were eliminated and did not return. In fact, we saw that the mice were protected. Even if we injected tumor cells, the cancer did not grow back because the CAR-T cells remained present in the mouse and continued to act to eliminate the cancer. These are the best results we have obtained in our long experience of over 20 years. We are very excited," emphasizes Arribas, who hopes that clinical trials, for which they already have funding for the first phase, can start next year.

Researchers are eager to continue their research. "Solid tumors are proving much more difficult to treat with CAR-T than expected. This is because immune cells do not access solid tumors as well as they do hematologic tumors, where these therapies are already being successfully used. In addition, solid tumors develop a whole range of strategies to inhibit the immune system and resist its action. But we believe that this dual-attack strategy can be very useful," says Arribas.

"We want to learn from successes and failures in solid tumors to design new strategies that allow immune cells to better reach the tumor and not be sensitive to the tumor's strategies to inhibit them. In this case, we used a dual therapy, but it is very important that when the trials in patients are carried out, we learn from both cases where there is an antitumor response and those where there is not, to see if an additional strategy can be introduced to improve effectiveness," he points out.

Initially, the trial will recruit patients with HER2-driven tumors expressing the p95HER2 protein who have exhausted all therapeutic options.

The research has been funded by the Carlos III Health Institute, the Spanish Association against Cancer, the BBVA Foundation through the Comprehensive Program of Immunotherapy and Cancer Immunology (CAIMI), and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF).