The COP29 in Bakú was saved in extremis with an agreement in the early hours of Sunday on climate financing. The adopted agreement, after long hours of negotiations hanging by a thread, raises the bar for wealthy countries to 290 billion annually, plus "consideration to increase funding for island nations and the least developed countries."

The approved text calls on "all actors" (public and private) to work together to achieve at least 1.3 trillion dollars annually by 2035, with a special mention to "emerging countries" (China, India, and Saudi Arabia) to make contributions "voluntarily."

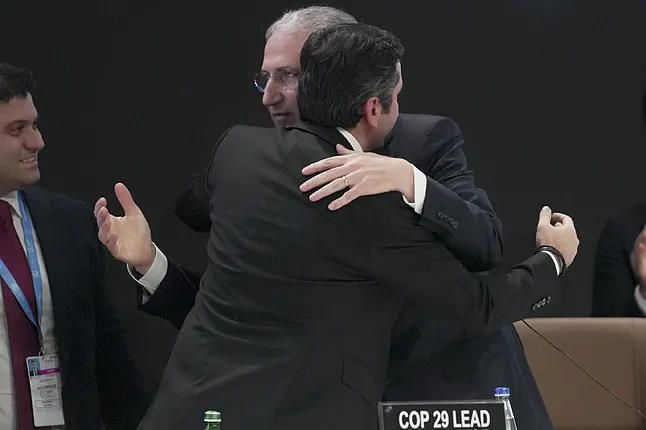

The agreement establishes the so-called Bakú to Belem Roadmap, where the COP30 in Brazil will be held, to continue advancing towards the New Collective Quantified Goal of 1.3 trillion dollars demanded by developing countries. COP29 President Mukhatar Barbayev, criticized during much of the summit for his inability to build bridges between poor and rich countries, finally wielded the gavel with relief.

In a plenary session interrupted several times to finalize the details of the negotiating text, the nearly 200 countries gathered at the Bakú summit finally sealed the agreement with which they set the new climate financing goal, replacing the previous one set at 100 billion dollars annually.

But in the end, consensus prevailed among the delegates of almost 200 countries, despite the criticism towards Barbayev afterwards for the swift final gavel without giving delegations much time to intervene. "It's not perfect, but I see some light," said Panama's spokesperson Juan Carlos Monterrey, who 24 hours earlier had described the penultimate draft of the text as "a spit in the face of vulnerable countries."

"No one wants to leave Bakú without a good result: the eyes of the world are on us, but time is not on our side," the COP29 President told the delegates when he was still not entirely sure.

New rules on carbon credits

Hours earlier, the plenary reached another significant agreement on rules for a global market for buying and selling carbon credits to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This is an issue on which states had not reached a consensus since the approval of the Paris Agreement in 2015.

As Barbayev explained, "Article 6 of the Paris Agreement will establish transparent and high-quality carbon markets through which countries and companies can work together to achieve their climate goals. In addition, Article 6 can save up to 250 billion dollars annually in the implementation of national climate plans."

The specter of a breakdown in negotiations - as happened at COP6 in The Hague in 2000 and COP15 in Copenhagen in 2015 - loomed over the Bakú summit for hours, the third consecutively organized in a petrostate (hydrocarbons account for 90% of Azerbaijan's exports).

Since its start on November 11, the enormous gaps between what developing countries were demanding (from one to 1.3 trillion dollars annually from 2035) and what developed countries were willing to offer in direct public financing (250,000 million dollars, raised at the last minute to 300,000 million) became evident.

Barbayev tried to rectify the situation with a second draft that included the distant goal of 1.3 trillion but at the same time exposed wealthy countries with the offer of 250,000 million, considered an "insult" or "a joke." The same text randomly left funding in the hands of private financing and new mechanisms (such as a possible global tax on fossil fuels).

UN Secretary-General António Guterres eased tensions by personally asking developed countries to raise their commitment to 300,000 million dollars annually. The European Union was the first to accept, and the rest of the wealthy countries gradually followed suit throughout the day, despite reservations from Canada, Japan, and especially the US, with the sword of Damocles of Donald Trump hanging over future climate negotiations.

The final text, also a call to China and Saudi Arabia to make "additional contributions," in direct response to the open debate at COP29 on the need to update the outdated classification of "developing countries" dating back to the beginning of climate summits three decades ago. Most of the funding will come from the European Union, the United States, Canada, Japan, the United Kingdom, Norway, Switzerland, Australia, and New Zealand.

The new financing goal would replace the agreement reached in 2009 at COP15 in Copenhagen, which set 100 billion dollars annually for climate financing and took thirteen years to materialize.