Margaret Atwood still has jet lag when she manages to connect to Zoom. "Sorry, I just arrived from Europe and my clock is running late," she apologizes with a radiant smile to 50 journalists from Spain and Latin America, where today Lost in the Forest (Salamandra) is released, the translation of her latest collection of stories. But this one is special because of its autobiographical tints. "I have never interviewed George Orwell, nor have I turned a snail into a person, and my mother did not pretend to be a witch," Atwood clarifies, laughing.

But before delving into her stories and after outlining a reflection on the history of literary utopias and dystopias from the 19th century to today, Atwood gives her opinion on the outcome of the elections in the United States: "Are we going to have a kind of Hitlerian dictatorship? I doubt it, but it depends on whether we can believe anything Trump says, because he lies so much... He says he will execute the army chief, that he will build concentration camps and put Democrats and immigrants in them...". She shakes her head with a smile.

The author of The Handmaid's Tale, one of the greatest dystopias ever imagined about the United States (and yet, everything she tells has happened at some point in history), analyzes Kamala Harris's defeat: "The fact that she was a woman and also of color has influenced. Many were afraid of losing their status and identity power with a Kamala presidency."

From neighboring Canada, the writer poses what may happen in the immediate future: "The United States has been the most powerful country in the world so far. Is it going to collapse? Are we witnessing a declining empire?". And she goes even further: "Another question is whether Trump will survive his term. How will his health be at 82 years old [he is 78 today]? Maybe at some point they will incapacitate him." This time she doesn't laugh, she says it very seriously.

Atwood is a fantastic 84 years old, dedicated body and soul to literature. At only 19 years old, while studying at university, she self-published her first poetry book, Double Persephone. Now she is writing her memoirs: "They are not a biography. Memoirs are things you can remember. And what you usually remember are stupid things or catastrophes, not if you had a great lunch... There's not much about my summer vacations, so to speak," she explains.

But meanwhile... In Lost in the Forest - which takes its title from the last story - she almost outlines a covert novel, a collection of snapshots of everyday life with domestic accidents, nighttime hobbies like cleaning the fridge or preparing jalapeño jelly. The protagonists are Tig (him) and Nell (her), a couple who have shared a whole life, even though they came from previous marriages, and who already appeared in another anthology from 2006, Moral Disorder (translated in Spain by Bruguera, but now out of print).

Tig loves birds, Nell loves butterflies: like her husband, the writer and ornithologist Graeme Gibson, and like herself, who dedicated one of her most beautiful poems to a Butterfly "with the blue of some eyes," an ode to her father's entomologist vocation (included in her poetry book The Door, also out of print: there is another Atwood to discover).

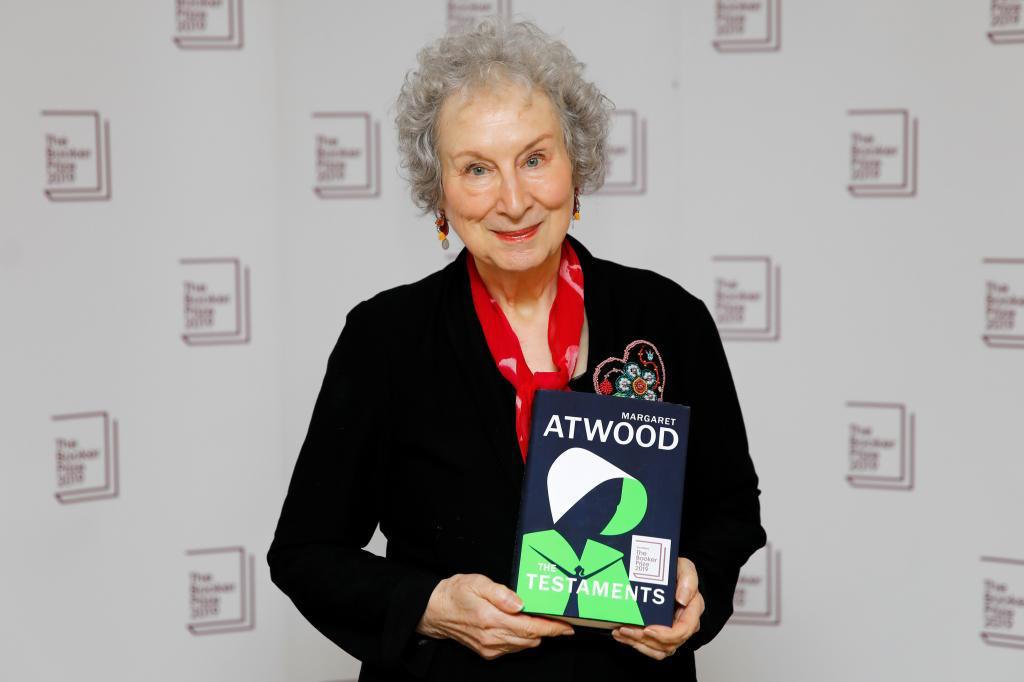

In the first story, First Aid, Tig dies. Like Graeme, who passed away in 2019 due to vascular dementia diagnosed two years earlier. He died in September, while Atwood was immersed in the promotion of The Testaments, the highly anticipated sequel to The Handmaid's Tale, which earned her the Booker Prize. The mourning for Graeme after almost half a century together goes from painful absence to luminous memories. And it resonates in almost half of the stories in Lost in the Forest: Tig and Nell star in seven of them, opening the book with 50 pages and, after an interlude of eight independent stories (which could be stories they tell each other after dinner), they return to close the volume with another 84 pages.

"What does memory have to do with happiness or sadness? Surely a lot: we remember sad and happy moments that have already passed. To what extent do we exist in a place and space that is no longer real?" Atwood poses.

The writer uses the third person to describe beautiful images of Tig and Nell sitting on a garden bench at sunset, in white bathrobes after coming out of the sauna he built himself to relieve his arthritis. They are holding hands and Tig is preparing her: "I won't be long."

But there is no devastating drama, thanks to Atwood's subtle irony. In reality, death hovers over almost every story in Lost in the Forest..., whether it's that of Hypatia of Alexandria, who narrates in the first person how a Christian mob flayed her alive, to that of the cat Smudgie, who dies of diabetes and to overcome the absence of the pet Nell rewrites Lord Tennyson's epic poem Morte d'Arthur with her cat as king.

Atwood also connects with George Orwell through a medium (Madame Verity) in a fun Postmortem Interview. "It was part of a series where living writers interviewed the deceased. I'm not dead yet, so they didn't interview me," she says. That's how she is: when she speaks and when she writes. "I have always liked Orwell a lot and wanted to ask him a series of questions. You will notice that he is still smoking, he hasn't managed to quit even in the afterlife although he knows it's not good for his health." And their interdimensional dialogue is one of the delights of the book.

There is more science fiction, from an octopus-shaped alien expert in intergalactic crises (The Impatient Griselda) to a contemporary witch (My Malevolent Mother) or a dystopian future where a sexually transmitted disease has spread worldwide and matriarchs are in charge of arranging marriages between uninfected young people to ensure survival (Pandemonium). Pure Atwood. Or Nell...