The farmer Pascal Mbanzagukeba, 33, addresses common health issues of his neighbors in the village of Kimikamba, southern Rwanda. Malaria occupies much of his volunteer work time, especially during peak season, when he handles an average of 15 cases per month among the 40 households and families under his care.

Mbanzagukeba has been trained by the Rwandan government to diagnose and treat malaria and is one of the tens of thousands of community health workers deployed throughout the country. His story helps understand why Rwanda has achieved great success in containing the disease and could achieve its eradication by 2030.

Between 2016 and 2022, the country of a thousand hills has achieved a reduction of over 80% in malaria infection rates and over 89% in deaths. Behind this success is a decentralized strategy to combat the disease through public education, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment activities. Community health workers play a crucial role in all these efforts, forming the cornerstone of the country's community-based healthcare model for its low-income population. Workers like Mbanzagukeba address preventable and treatable diseases among their neighbors. It is estimated that there are around 58,000 of these volunteer workers for a population of 13 million inhabitants.

Malaria is a devastating disease, affecting mainly infants, young children, and pregnant women. It is transmitted through the bite of a mosquito infected with a Plasmodium parasite. If left untreated, infection by P. falciparum, the deadliest and most prevalent parasite in Africa, can lead to severe illness and cause death within 24 hours. In 2022, there were 249 million cases and 608,000 deaths worldwide, with the majority occurring in sub-Saharan Africa.

In Rwanda, over 90% of malaria cases are managed within the community; around 60% by health workers and to a lesser extent by health posts and centers. The humble mud house of agent Pascal Mbanzagukeba hosts a makeshift clinic consisting of a bed, some toys to entertain the children he treats, and medical supplies provided by the Ministry of Health.

In addition to malaria, he also handles diarrhea in children under five and pneumonia. Not all these health workers can afford to dedicate a room in their house to this voluntary work, notes Mbanzagukeba, who states that he has done so by choice and without significant investment. His single-story house, by Western standards, is not spacious: he has sacrificed space from the 80 square meters where he lives with his wife and young children. The Rwandan government provides modest incentives for community health workers. Mbanzagukeba mentions that he does not receive financial compensation for this work and earns his income from farming. He expresses gratitude for having a mobile phone with coverage and a flexible job that allows him to schedule patient appointments at his home or leave the field in case of emergencies. Sometimes he has to make house calls to patients: "on those occasions, I usually have to take long walks," he admits.

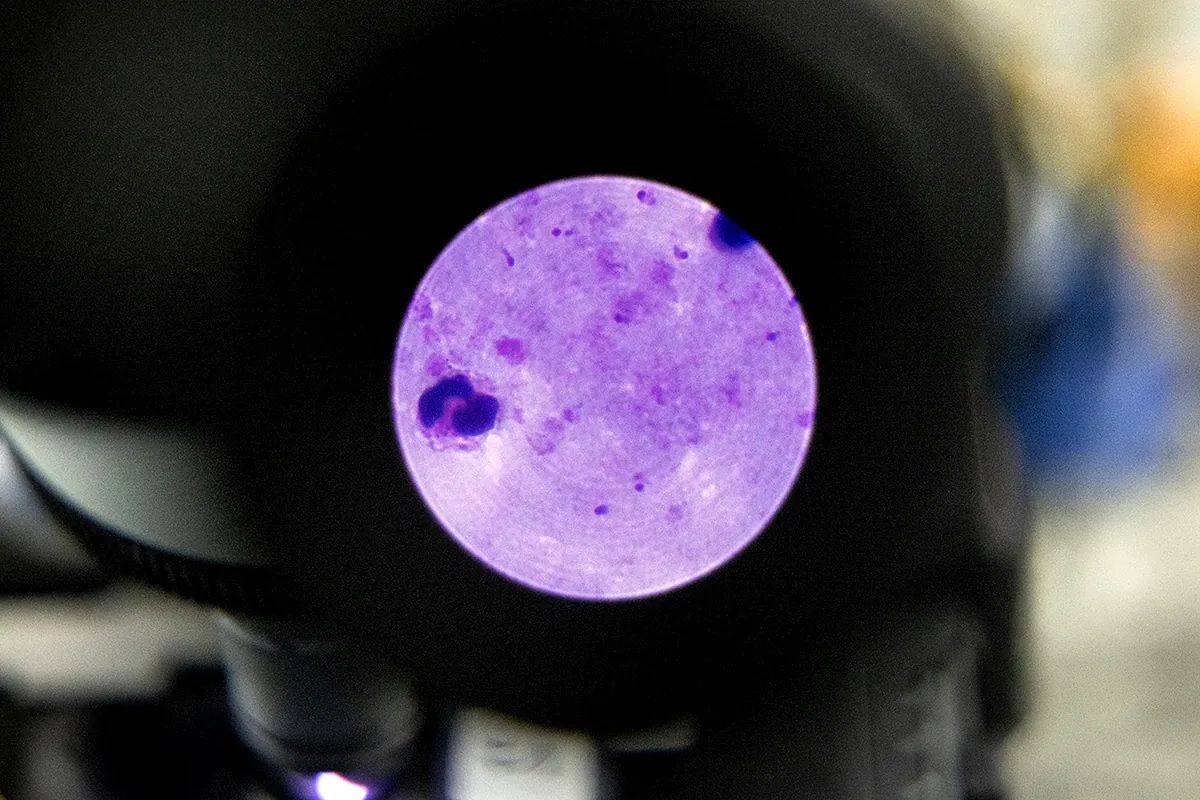

Any suspicion of malaria must be confirmed with rapid tests, and if the result is positive, medication should be initiated promptly. "I have not had malaria myself, but my family members and neighbors have, and I know how serious it can be," says Mbanzagukeba, who ensures that patients take the first pill in his presence, explains how to continue the treatment, and stresses the importance of not discontinuing it once they start feeling better to prevent relapses. "It doesn't happen often, but some return with malaria after a month. If that's the case, they are referred to a health center because community health workers are not authorized to treat them again." Mbanzagukeba refers his patients to the nearby Ruhuha Health Center. There, they handle complicated and severe malaria cases, and patients with gastrointestinal symptoms are hospitalized for at least 24 hours. The facility has an ambulance, a small inpatient unit, a microbiology laboratory, and a pharmacy. Of the 18 healthcare workers, half are nuns. In Rwanda, it is estimated that there is a community health center like Ruhuha for every 25,000 people, and these clinics work in coordination with community health workers.

The only requirement to be a community health worker in Rwanda is to be able to read and write. Mbanzagukeba has medical documentation and algorithms on the steps to follow with patients. He emphasizes that a significant part of his work is case recording, for which he has several notebooks that he fills out by hand. However, volunteers must be known and respected in their community, as they must go through the process of being elected in an assembly held among the neighbors themselves. "Being a community health worker is a vocational job," he declares, stating that he feels rewarded because the impact for him is "enormously positive": "I like that they trust me and refer to me as the community's doctor."

"Community health workers are the backbone of Rwanda's healthcare system and are essential for disease control," notes Elias Sebutare, Director of Programs at Health Builders, a local NGO working with the Ministry of Health to train community health workers and improve the healthcare system for rural communities.

After a sharp increase in malaria cases in 2016, one of the flagship measures promoted by the government was to strengthen the community healthcare network, with community workers playing a leading role. Community health workers handle 60% of malaria cases, compared to only 15% in 2016. In recent years, the country has experienced significant fluctuations in malaria numbers: after nearly eliminating the disease between 2010-2011 (with 36 cases per 1,000 inhabitants), it rose to 409 per 1,000 in 2016, when 5 million cases were recorded. In 2022, the incidence dropped again to 76 cases per 1,000 people. "The increase in cases in 2016 was due to climate change, low coverage of disease control interventions, insecticide resistance, declining immunity, and the impact of development activities such as irrigation projects for agriculture," explains Aimable Mbituyumuremyi, head of the National Malaria Program at the Rwanda Biomedical Center, the national health policy implementation agency. In 2016, the mass distribution of insecticide-treated mosquito nets began; controlled indoor spraying activities and monitoring of mosquito resistance to insecticides were implemented, along with the collection and use of data, like those recorded by agent Mbanzagukeba, for the implementation and monitoring of these interventions.

Thanks to all these activities, Rwanda is one of the few countries on track to achieve the World Health Organization's Global Technical Strategy (GTS) goal of reducing malaria incidence by 75% by 2025 compared to 2015. However, Mbituyumuremyi warns against complacency and highlights the risk of losing the ground gained. A primary threat is the parasite resistance to artemisinin-based combination therapies, the standard of care.

To address this threat, Novartis laboratory, which launched the first fixed-dose artemisinin-based combination therapy in 1999, is working on a new generation of malaria drugs. To date, the company, in collaboration with the WHO, has provided over a billion treatments of its artemisinin-based combination therapy, including over 450,000 of the pediatric formulation, "most of them non-profit," explains Caroline Boulton, global head of the company's Malaria Program. The laboratory is developing three new compounds for severe and uncomplicated malaria in adults and children: "They belong to new classes of drugs that target the parasite differently from current therapies."

Alongside the work of agents like Mbanzagukeba, finding new weapons to combat the infection is crucial to achieving a definitive end to the disease.