Elia Kazan said she was an actress who lived in a cloud of dramas. Bette Davis pointed her out (live on Johnny Carson's show) as the only actress she would never work with again. She added: "Anyone you ask in Hollywood will tell you the same." Her beloved and always devoted son describes her (this time in the present) as a normal person who spent half her life wanting to be a star to dedicate the other half, already as a star, to wanting to be a normal person. And, to dispel any doubt, she said of herself that few things were as difficult as working with... her. It is rare, if not simply unheard of, for a biographical documentary about a Hollywood star to start by denigrating its protagonist. Faye, the film directed by Laurent Bouzereau that will premiere on July 13 on Max, does just that. But with class. A lot of class.

Barely appearing on screen Dorothy Faye Dunaway (Florida, 1941), that is her full name, the now elderly and perfect baby at the same time (like Úrsula Iguarán in One Hundred Years of Solitude) complains about the camera angle, curses the sofa she is sitting on, and scolds the director for not being in his place. And the water. "I asked for a glass, not a bottle." However, a furtive glance at the camera reveals the artifice: Faye is playing herself, Faye is being Faye, or rather, Faye is playing the Terrible Faye (The Dreaded Dunaway) that Jack Nicholson baptized her as.

If this new documentary contributes anything to the shared imagination, it is neither a myriad of new data nor a revision of the actress's figure. What Faye really excels at is in its ability to give meaning to the tragic feeling of a life and a career essentially tragic. The star of at least three essential films to understand the recent history of cinema and History (with a capital H) surrounding the history of cinema itself (Bonnie and Clyde, Chinatown, and Network) was (and still is) a person of prodigious talent, meticulous to obsession, temperamental beyond the possibilities of all those around her, and, moreover, a kind of catalyst for each of the milestones of our time.

She was the first to embody the most violent and powerful of women in the most violent of scenes ever filmed, and she did so when the trauma of the assassinations of John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Martin Luther King took the breath away from an entire country. She was the first to tackle the darkest of characters in the most corrupt of worlds, and she did so when Nixon was revealed as the most deceitful of presidents. She was the first to embody a television executive without the slightest hint of scruples when mass media was already showing what it could mean for a democracy to be hijacked by ratings. Lumet demanded that Dunaway, for the role of the TV executive, not show any of the vulnerabilities she always displayed. And so she did. Sending chills down our spines.

With those three characters -- with Bonnie Parker, with Evelyn Mulwray, and with Diana Christensen according to the handwriting of directors Arthur Penn, Roman Polanski, and Sidney Lumet -- it would have been enough. But she was also the most intelligent and glamorous inspector Vicky Anderson in The Thomas Crown Affair alongside Steve McQueen; she was the terrifying gaze of Laura in Eyes of Laura Mars; she was the forever defeated Wanda Wilcox alongside the best Mickey Rourke in Barfly as dictated by Barbet Schroeder, and, above all considerations or sense of measure, she was Joan Crawford in the worst and best (or best worst) melodrama ever brought to the screen. Indeed, Mommie Dearest, by Frank Perry, is folly in its most precise form. And even sensible.

Faye delves into her bipolar disorder and years of alcoholism. But it does not showcase them as excuses for anything. In reality, Faye's explosive behavior is not so different from that of many celebrities like her. The issue, and here she was also a pioneer, is that she was the first actress who, whether due to her character or her illnesses, made her star condition the biggest headache of all. Until then, that had always been a privilege of men, not women. And that is when the film succeeds in showing that what in her male colleagues was always considered a personality trait, in her case it was hysteria; what in actors passed as a consequence of their talent, in her case it was simply caprice. And from there, from the most basic sexism, came the punishment. At one point, her son Liam Dunaway O'Neill wonders if depression was a radical part of her. "If she hadn't suffered so much, would she have been so good?" he asks, and who knows if in that doubt he hits the nail on the head. She affirms that Elia Kazan taught her that her feelings "were her strength" and then corrects herself: "In any case, I was always responsible for my actions." However, hearing her speak candidly about her struggles with mental illness and later with alcohol sheds a new light on the furious mystery of Faye Dunaway.

Furthermore, the documentary punctually follows her career convinced that she was "all her characters in one". Producer Sam Spiegel discovered her on the alternative stages of New York and made her debut in The Happening in 1967. Then came Hurry Sundown by Otto Preminger, and next, Bonnie and Clyde at the insistence of the director and Warren Beatty. And, hand in hand, the revolution. What follows has much of predestination. And a bit of penance. Her struggles to be the thinnest, the most tormented, the most perfect, led her into a very painful labyrinth where dazzling episodes emerge, such as that sublime love scene (sublime love and sublime scene) on the chessboard in The Thomas Crown Affair; or particularly embarrassing episodes like when, without warning, Polanski decided to pluck a rebellious hair from her during the filming of Chinatown (no one blasphemed as well as she did, the Dreaded Dunaway), or essentially tacky (or kitsch) episodes like the one she identifies as the biggest mistake of her career: her portrayal of Crawford in a film that was first vilified only to later acquire cult status against her will. It is moving to see Mara Hobel (portraying young Christina Crawford in some of the most exaggerated scenes of child abuse in the film) get emotional at the poignant memory of the purest and even disastrous emotion.

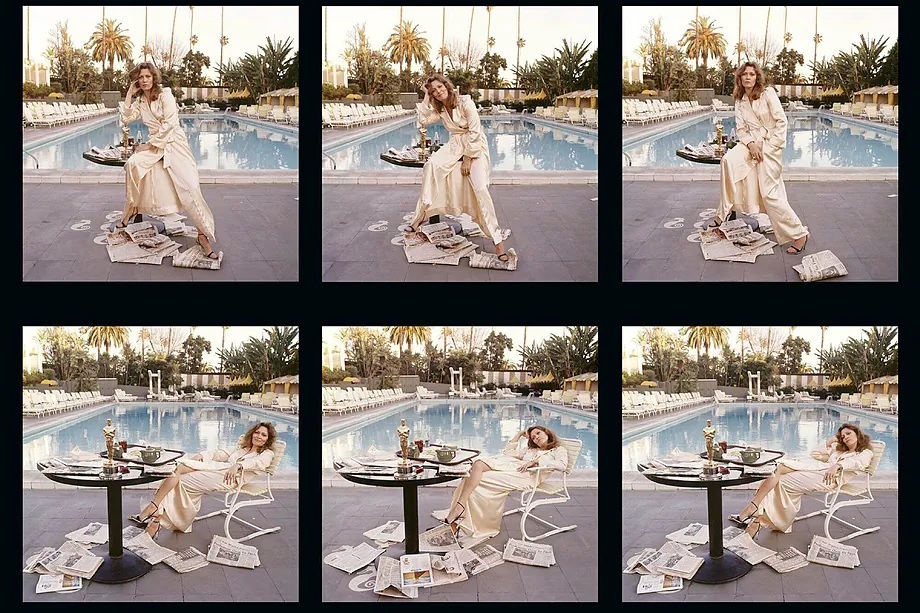

Faye Dunaway disappeared in the 1990s only to return in the 2000s with directors like James Gray or Emir Kusturica. She also directed a short film and, along the way, her long-cherished project of bringing the play Master Class to the screen, in which she herself played Maria Callas, remained unfulfilled. All of this is enthusiastically and painfully documented in the film. Just as painful is the memory of her great love, Marcello Mastroianni, with whom she maintained a long and exhausting clandestine relationship. From one of her husbands, the photographer Terry O'Neill, remain what are probably the 12 best snapshots ever taken of a Hollywood star. There she is, at six in the morning on March 24, 1977, with the Oscar just received for her work in Network by the edge of the pool. At her feet, the entire world printed in the newspapers of the day. And in the middle, Faye, the untamable Faye.