Out of the nearly 300,000 new cancer cases that will be detected this year in Spain, 3.5% will be in the pancreas. An important number considering that survival rates are very low, close to 10% over the first five years. Mortality has increased in both sexes over the last decade: 8,140 compared to 6,278 in 2014, due to the rise in incidence to 9,986 cases in 2024, compared to 6,367 a decade ago.

Traditionally, this tumor affects people over 60 years old. However, "some studies suggest that the diagnosis in younger people is increasing, which could be related to lifestyle habits and the increase in risk factors such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, which are appearing at younger ages," says María José Safont, a member of the Board of the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM).

Therefore, we are facing a significant health problem, despite not having a high incidence in the population, it will be the third most deadly cancer in Spain this year and, by 2030, the second. Figures significant enough to dispel the "poor cousin" stigma that weighs on it.

"Today, pancreatic cancer is one of the most important challenges in the field of Oncology. Worldwide, there is no lack of interest or funding," emphasizes Mariano Barbacid, AXA-CNIO Professor of Molecular Oncology and Director of the Experimental Oncology Group at the National Center for Oncological Research (CNIO). Another question is whether this momentum is felt here in our country. The researcher points out that, "in Spain, within our endemic limitations due to the lack of public funds, the CRIS Foundation against Cancer is making a very important effort to finance competitive groups working in this area."

One of the researchers who has recently benefited from these contributions is Meritxell Rovira, from the Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (Idibell). She leads a project funded by this institution that aims to detect pancreatic tumors, the most lethal and resistant to advances in treatments, through a blood analysis.

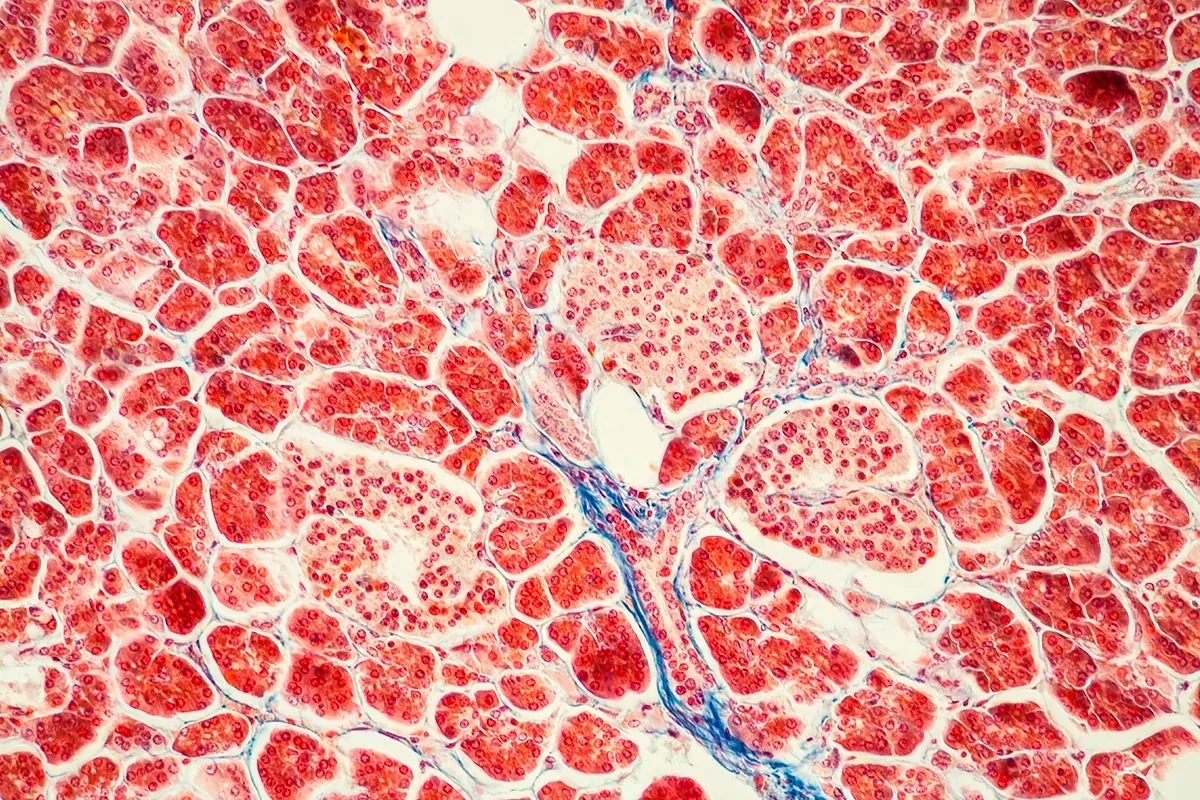

"As we are facing an extremely heterogeneous cancer, we are trying to develop an atlas with all cellular elements, alterations, and mutations," explains Rovira. She adds optimistically, "Until recently, funding for pancreatic cancer research was almost 2% of the total. We are dealing with a rare, highly lethal cancer. But in the last decade, that percentage has slightly increased, resulting in a rise from 8% to 12% in survival rates."

"We are facing a very heterogeneous cancer. We are seeking the development of an atlas with all its cellular elements, alterations, and mutations."

Clues and time are what oncologists need to recognize patients and offer them effective therapeutic options. "Unfortunately, none of the three new therapies developed in the last 25 years: precision medicine, immunotherapy, and CAR-T therapies have had a significant impact on the treatment of this type of tumor so far," laments Barbacid.

This is what is available "in the armamentarium of such an aggressive tumor as pancreatic cancer," insists the CNIO researcher. The only approved therapies so far are based on old chemotherapy as described by Barbacid: "Folfirinox, a highly aggressive treatment consisting of the combination of four cytotoxic agents, gemcitabine another cytotoxic discovered almost 30 years ago, and Abraxane, which is nothing more than a new formulation of the old taxol."

Pancreatic cancer is difficult to detect and treat because symptoms tend to appear in advanced stages, "when the tumor has already grown or spread," indicates Safont, also a medical oncologist at the General University Hospital Consortium of Valencia. One of the obstacles is its location: deep in the abdomen, "which hinders detection in physical exams," she points out.

Additionally, "the early symptoms are usually nonspecific, such as abdominal pain, weight loss, or fatigue, which can lead to late diagnoses. Its aggressive behavior also makes it difficult to treat effectively," argues the oncologist about the complexity of early diagnosis.

With limited treatment options and difficulties in reaching early stages, what can the thousands of patients who will be diagnosed in the short term expect? "The key to making therapies more effective lies in better understanding the molecular characteristics of pancreatic cancer and how it behaves at the genetic level. This has led to the development of therapies targeting specific mutations, such as KRAS," states the SEOM oncologist.

"Early diagnosis and personalized treatments are also important to better adapt to the tumor's characteristics in each patient," she adds. At the time of diagnosis, less than 20% of patients will be eligible for surgery, given the advanced stage of the disease. After surgical intervention, survival is usually 10-20 months.

Perhaps, first and foremost, while clinicians seek early detection solutions and effective therapies, it would be important to eliminate avoidable risk factors. "We have identified the risk factors: obesity, smoking, and diabetes, clearly related to this neoplasm," says Safont. There are also genetic factors that may influence the increased incidence of cancer, as the oncologist points out, "although it is mostly a sporadic disease. However, many cases occur in individuals without direct family history and are more the result of a combination of genetic and environmental factors."

Challenge: Storming the "Tumor Castle"

The challenge facing scientists is to attack its domains. The complex physical location is combined with the fortified system built by the tumor in this organ: a sort of medieval castle, complete with a moat, where the immune system defenses along with current treatments barely manage to penetrate successfully.

"By identifying the enzyme ELOVL6, chemotherapy more easily crosses the tumor cell membrane, enhancing its action."

"Pancreatic cancer is what is known as a 'cold tumor,' meaning it has few infiltrated immune cells and therefore immunotherapy usually does not work," argues Rovira. In this regard, Barbacid explains the therapeutic approaches, which "focus on eliminating or at least inhibiting the tumor microenvironment or permeabilizing the dermoplastic stroma." The CNIO researcher states that "there was much hope that KRAS inhibitors could have a significant impact since this oncogene is responsible for initiating this type of cancer in 95% of cases."

This week, two new tactics were revealed with which researchers are planning invasions in cancerous areas. Both have Spaniards among their ranks and have been published in high-impact scientific journals.

On one hand, a study from the 12 de Octubre University Hospital and the Francisco de Vitoria University, both in Madrid, published in Nature Communications, has shown that it is weakening the castle walls. In other words, thinning the membrane of the tumor cell, making it more permeable and allowing chemotherapy to penetrate much more effectively. Víctor Sánchez-Arévalo, head of the Molecular Oncology Group at the Francisco de Vitoria University and and the Hospital 12 de Octubre (UFV-H12O) and principal investigator, points to the target that makes it possible: the enzyme ELOVL6, "responsible for elongating the chains of fatty acids present, among others, in the plasma membranes of cells."

The expression of this biological catalyst is regulated by the oncogene c-MYC, "which is usually altered and overexpressed in pancreatic cancer, implying that there are also high levels of ELOVL6." "Its inhibition or silencing, both by chemical and genetic methods, alters the physicochemical properties of the cell membrane, making it less rigid and more permeable. As a result, chemotherapy penetrates it more easily enhancing its action," details Sánchez-Arévalo.

The researcher points out that the effect is mainly observed in those chemotherapies that use nanoparticles to deliver drugs against tumor cells, such as paclitaxel, a common medication against this cancer. Consequently, "it would be possible to achieve the same effect on cancer cells with a lower dose of chemotherapy, also reducing its toxicity," he emphasizes.

On the other hand, PNAS has published a joint work from the Research Institute of Hospital del Mar, IIBB-CSIC-IDIBAPS, Mayo Clinic, Institute of Experimental Biology and Medicine (CONICET, Argentina), and CaixaResearch Institute that opens the door to new strategies. Here, the assault would occur thanks to the identification of one of the members of the crew, responsible for its aggressiveness: an unknown function until now of the protein Galectin-1 within the nucleus of fibroblasts.

"This stroma is considered a key piece, as it interacts with cancer cells, protects them and prevents the action of drugs. In addition, stromal cells, particularly fibroblasts, produce substances that facilitate neoplastic growth and spread," explains Pilar Navarro, from Hospital del Mar and IIBB-CSIC-IDIBAPS.

This team of scientists has tested this theory on patient samples, which has allowed them to verify the presence and function of Galectin-1 in the nucleus of fibroblasts. Along with this, they have conducted in vitro experiments with human fibroblastic cell lines, where they have investigated the effects of inhibiting both the protein and the KRAS gene, observing a deactivation of these cells. This creates a gap in their ranks, meaning it would prevent fibroblasts from collaborating with tumor cells.

Gabriel Rabinovich, a researcher at IBYME (CONICET), outlines the following steps. "We will explore therapeutic combinations that allow inhibiting Galectin-1 both extracellularly and intracellularly. In fact, this protein also participates in key processes for the tumor such as blood vessel formation and resistance to immunotherapy. Therefore, this strategy becomes particularly important considering the multiple antitumor capabilities of inhibiting this protein."

Barbacid concludes that "bringing our immune system to tumor cells, that is, something similar to what we know as immunotherapy or finding ways to overcome tumor resistance mechanisms to personalized therapies will be two important milestones in fighting against this terrible disease."