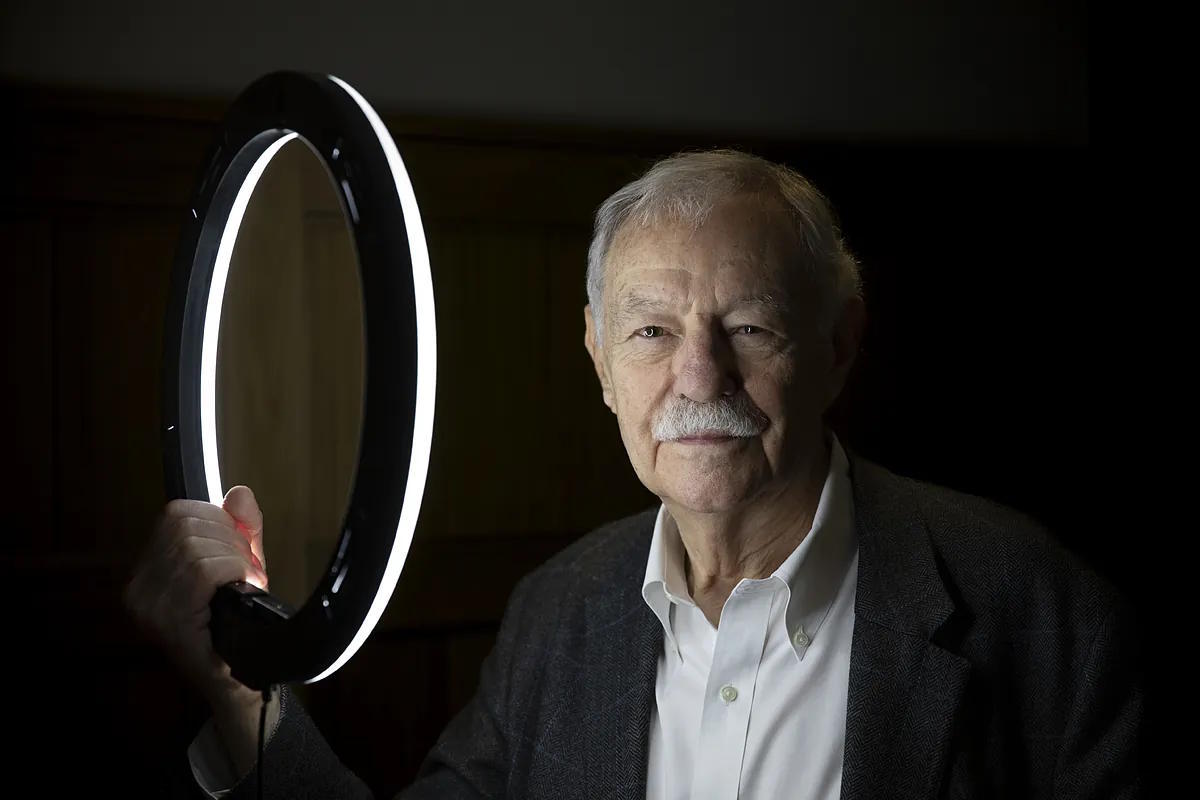

'The Truth about the Savolta Case', one of the key works of contemporary Spanish literature, turns 50 and Eduardo Mendoza (Barcelona, 1943) reminisces in a café in the center of Madrid.

It's effortless for him, still active, in great shape, and as lucid as ever despite not denying the passage of time. "The procession goes on inside. This is a novel that is very present, with new editions coming out frequently, but what truly impresses me are not the 50 years of the book, but the 50 years of myself. That's the issue, the book will manage," he laughs.

At least 50 well-lived years have passed.

Very well-lived. I have no complaints and I am delighted with life. The truth is that time would have passed for me regardless, and I wouldn't have a book for which I feel a special affection. It's a novel I wrote with all innocence and absolute freedom because I didn't know if it would be published, and I assumed that even if it was lucky enough to be released, no one would read it. I wrote it thinking about what I would do when it failed.

It wasn't his best moment as a fortune teller.

No, luckily I found another job. I cherish 'The Case Savolta' like a first child even though it wasn't really. I had already had others that I had abandoned, thrown away, or sent to the foundling home because they weren't good. I had even taken a short humorous novel to publishers that they didn't want to publish, fortunately.

Have you ever been tempted to recover it?

No, quite the opposite. I got rid of it, burned it, destroyed it precisely to avoid the temptation. So, with 'The Case Savolta,' I didn't expect much, but I was lucky that it was well-received... and also unfortunate that I found myself in a situation where the first novel created unheard-of expectations. The critics said, "He is renewing Spanish literature." And I thought, "Oh my, I didn't want to renew anything, I just wanted to write a book." And then that label of "the novel of the Transition," it seemed like the Transition depended on what I was going to write from then on. Fortunately, at that time, I was living abroad, in New York, so it didn't affect me much. If I had been living in Spain, it would have been tough.

You wrote it while Franco was still alive.

Yes, it went through censorship and all, but just as Franco died, this novel appeared and became the first of the Transition. It is also a thick, ambitious novel, with political content, the recovery of anarchism and social movements... It had the ingredients to play this symbolic role that was completely fortuitous, but there it is. It worked out very well for me, but it also created a responsibility that I was not willing or prepared to assume. I thought, "What do I do now?" The pressure was literary; personally, nothing happened because in those years being a recognized writer meant being absolutely nothing. No one recognized me on the street or knew who I was. Which famous writers were there then? Cela, Delibes, and that's it. It didn't bring in much money because very few copies were sold. In my case, more than I thought, but no one was living wonderfully by writing.

Do you remember how many copies 'The Case Savolta' sold back then?

About 7,000 copies, but 2,000 was already a bestseller. 7,000 was unheard of and could represent around 14,000 pesetas, which was a lot but didn't change your life. Literarily, I felt a bit inhibited by the expectations. I had already started writing something else, but I stopped because I didn't know how to continue. Until, just for fun, I wrote 'The Mystery of the Enchanted Crypt,' which was something very different, much lighter, and that's when I calmed down. After that, I was able to write another ambitious novel like 'The City of Marvels.'

There are few writers who have mixed high literature with light literature so well.

It just turned out that way. I combine more ambitious novels with jokes. Before, writers wrote dramas and comedies without problems, Calderón de la Barca, Lope de Vega... Combining both doesn't seem so crazy to me. I have written serious novels with varying success, while the light comedies come naturally to me, I enjoy writing them, and they sell like hotcakes. They allow me to buy what I value most, which is time, be my own boss, do what I want, and dedicate myself to what I like. That's thanks to 'No News from Gurb.'

Sometimes, it seems that great writers are ashamed to admit that they want to sell a lot.

Selling is extremely important, it's a fundamental goal. The day you decide to leave everything and dedicate yourself solely to writing, the first thing you have to trust in is that your ideas will sell because you have a family, and it's a complicated decision. Money is crucial because novelists, despite posing as artists, also have bills to pay. Rent, electricity, phone bills, children's schools... Well, well, well! And there's no way to get paid under the table because we expose ourselves in the book promotions: "50,000 copies sold," in big letters [laughs].

I heard you once say that you would have liked to be apolitical, but you have never achieved it.

Yes, in the end, politics always somehow comes into play. What I have always tried to do is to be on the streets; openly political, I have only written some newspaper articles and a little book about Catalonia during the difficult times of the 'process.' Not so much to take a stand, my position on nationalism as something anachronistic is clear, but to explain abroad what was happening. I was called by the BBC, they asked me about what was happening in Catalonia, and they had no idea, they didn't understand anything, they were still stuck in the Civil War and Franco era. I wanted to explain that the people involved in this, for or against, don't know who Franco was, they don't know who Adolfo Suárez was, they were born lucky with Aznar. Apart from that essay, it's not so evident in the novels, but I always try to reflect some reality in them.

What does the author of 'the novel of the Transition' think about all the current debate surrounding it?

I have the highest concept of the Transition that one can have. At that time, we imagined all the scenarios that could happen, the good, the bad, and the mediocre, and what actually happened was fantastic, the best that could have happened. Because people now forget that we were threading a very fine needle, that there were serious possibilities that everything could have gone terribly wrong. As I am quite old now and the old man who tells stories, this morning I was crossing Alcalá and remembered that at that time, crossing this street with a friend, we ran into one of those far-right groups that roamed the city, and we had to run away to avoid getting beaten up. Now they approach you to take a selfie, and before they attacked you to beat you up. We have come out way ahead, I would say.

Well, that's clear.

That's why to those who complain about the Transition from the comfort of 50 years of democracy, I would say to be more generous with what was achieved in those circumstances. Think about the situation we were coming from and appreciate how well we are now, largely thanks to what was done back then. I hear too much that Spain is in a terrible state, that everything is a disaster, that life is better in other countries, and it's a lie, I never tire of saying it. Until recently, I lived between Barcelona and London, I have lived a lot in the United States, I know Germany well, I have worked in Switzerland. Go see how life is there and see how it is here. You'll be surprised.

Now even the Welfare State is being discussed.

Yes, it would amuse me if these Trump or Musk fans had a minor health problem in the United States one day. I have an American friend with residency in Spain who had a heart problem, and the public health system treated him, operated on him, and solved it for free. When it was over, he inquired about how much it would have cost him to live in the United States: over a million euros, which, of course, he doesn't have. He would have died or robbed a bank.

In Spain, we have our own issues. There is a resurgence of Francoism among the youth.

Well, they talk about Franco, but it's not Francoism because it's like if I said how great it was in Primo de Rivera's time. It's just talk. What's trendy among a sector of the youth is to criticize democracy to go against the system because they do have it tough in many aspects. I grew up in a terrible Spain, but when I finished university, I found a job, and with my first paycheck, I rented a central apartment in Barcelona. And I lived reasonably well, I earned peanuts, but it was enough for that, for drinks, dining out, buying clothes, and living a good life. Now that doesn't happen, and they are scared and angry, that's why they join anything that sounds like going against the system: it happened with the far-right as it did with separatism. 80% of those who took to the streets would have done so for anything. They could wave flags, burn some dumpsters, and vent their anger.

Now Franco is being talked about non-stop, and in reality, it is a period that, for example, those of us born in democracy have barely studied.

Francoism, the Transition, and what has later been called disenchantment are not studied, and no one has explained them well. That has indeed been a mistake. I have never become disenchanted with the democracy we have achieved. I believe we have lived through a good era and in a way, we are still living it, but we are neglecting it. Tranquility is very important for the Welfare State, being able to walk down the street without looking around in case you get thrown into a car and kidnapped, as happens in so many countries. Until now, Spain has always maintained this, despite changes in governments. There has been an agreement that the system was non-negotiable. In Italy, they always told me what a political example Spain was because the PSOE was in power, then the PP, and nothing serious happened. That stability, that continuity, has been wonderful, and I don't know if we are still following that same idea now.

Are you worried that we might fall into instability?

Yes, because we have a Government with many problems governing due to its composition, and an alternative would be difficult because if the PP wins, they will have just as much trouble, and furthermore, the far-right could come in. I don't know what to think, the truth is I don't understand anything. Immigration is a very big problem, especially localized in some areas and social sectors. In the neighborhood where I live, there are few immigrants, they are lovely, and we are all friends. For me, it's very easy to say that everything is fine, but where the core is, in some towns and industrial areas, there is a serious conflict of interests and cultures. And the left has somewhat neglected the working class, which used to be their clientele. There is no longer a class struggle. Of course, the working class is in China.

When one appears in textbooks, do you feel eternal?

Not at all. Being in textbooks and being required reading in high schools is the most important thing that has happened to me because it meant that every year there were thousands of readers who had to buy my books [laughs]. It also means that several generations have started reading with me. I have met many people who tell me, "Your book was the first one I read." And not only that, even writers say, "I decided I wanted to be a writer because I read your novel in school." What a responsibility, right?

Well, the ego will appreciate it.

No, because also, regarding these stories of legacy, I believe there is a new phenomenon now: when a writer dies, they completely disappear.

They don't erase you from the book.

But they don't read you. Others have come out, and that's it. I have seen it because I am the last one left from a generation that was fully present, and as they have died, they are forgotten. Now they take me to places like the Atapuerca man because, of course, I knew García Márquez, was friends with Vázquez Montalbán, Marsé, Javier Marías, Juan Benet... There is no one left, but you know what?

What?

When I die, they can do whatever they want with me, forget me, erase me, consider me whatever they want. It doesn't matter to me. And for my children, it's better if I disappear because it's not good to carry around the old man's mummy.