The steps of Fernando Giráldez (Buenos Aires, 1952) seem to move on their own through the Prado Museum. They know where they are going, so we quickly adjust our steps to his to be guided by this Medicine doctor towards some of the most emblematic works of the museum. He is going to show us some of the best paintings in History, but from a different perspective. "We seek the neuroscience hidden in painters, what they teach us about the subject," he says about the purpose of our visit as he heads towards the labyrinth of rooms from the entrance of the Jerónimos.

Giráldez has just published his first popular science essay, A Neuroscientist in the Prado Museum (Paidós). And the neuroscientist mentioned in the title is him, so we are letting ourselves be guided through a space and a subject that our guide knows better than anyone. "Two and a half or three years ago, I practically lived in the museum," he confesses about his research. He wanted to understand how loose brushstrokes on a flat surface become a meaningful image for the observer. He discovered that the great masters had grasped the functioning of the brain centuries before scientists. "Classic painters are intuitive neuroscientists because they need to figure out the rules with which we see and build the world to give us back illusions," he explains as he passes by The Garden of Earthly Delights by El Bosco. "In a way, they have been able to reverse engineer the visual system. They explore how they themselves paint and, from there, end up discovering which techniques are best to recreate space or convey dynamism."

During the visit, there is no time to squeeze among the group that looks on in awe, but in the book, he does dedicate some observations to the scene we saw from the corner of our eye: "El Bosco invents strange, extravagant, anomalous, or unreal objects. It is a masterful blow from a perceptual point of view because it challenges the brain to categorize within its limits."

Know that if your head has been smoking trying to identify everything in the altarpiece, the fire was in your face neurons and object neurons: they are the ones doing that job.

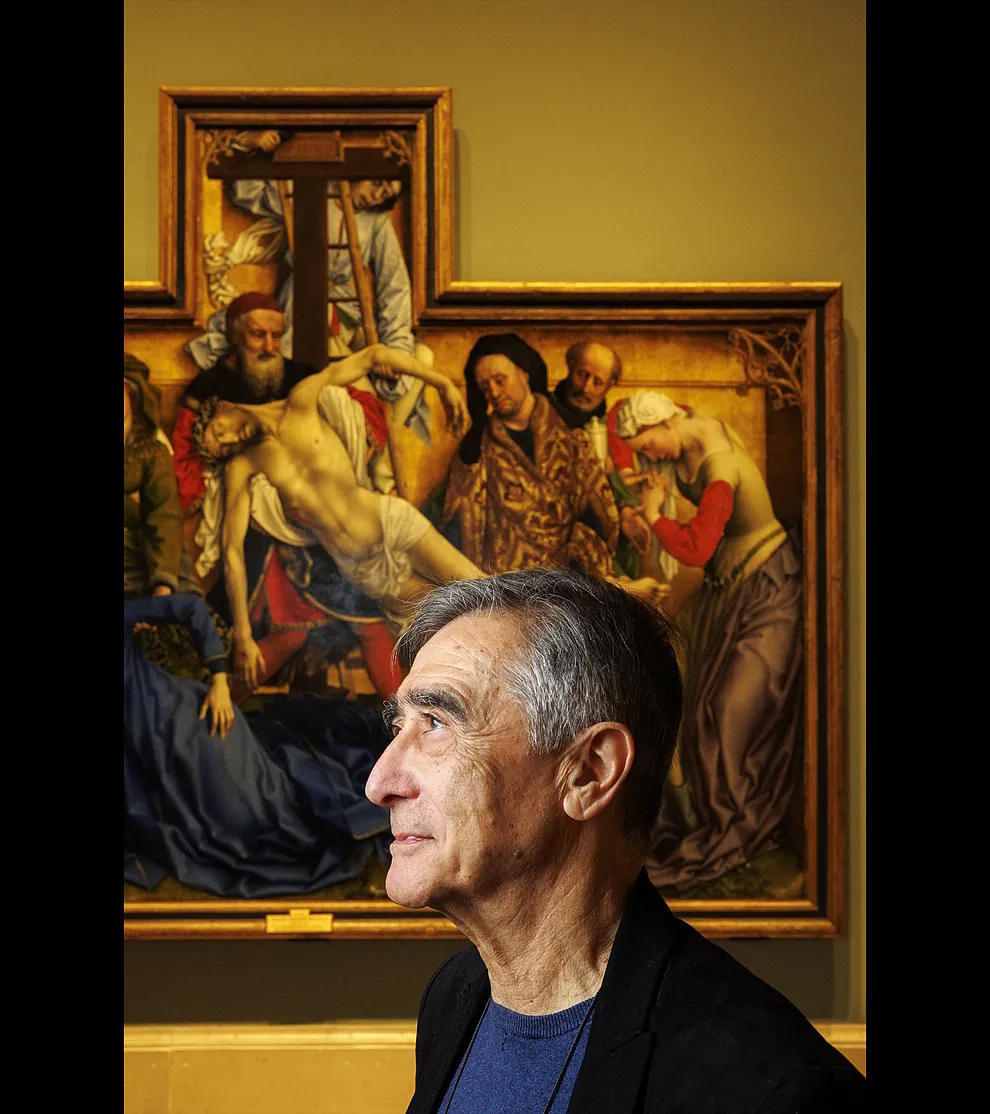

Giráldez soon leads us to the first painting on our itinerary: The Descent from the Cross by Rogier Van der Weyden. But, of course, using this verb properly requires a previous question...

- Reconstructing in the brain what is outside of us. That is not obvious at all, it depends on many things, and above all, on millions of neurons.

The eyes are part of the process, but they function more as an extension of our gray matter; it would be something like the periscope that the brain, trapped inside a skull, needs to deploy outward. 2% of its retina is the fovea, and we use it to distinguish colors and shapes sharply; the remaining 98% is the peripheral retina, capturing things in low resolution and detecting space and movement. Also, keep in mind another idea borrowed from Giráldez's book: shape and color are processed in one part of your brain; space and movement in another.

"Seeing is reconstructing in the brain what is outside of us and depends on millions of neurons"

This helps to better understand what the scientist explains in front of Van der Weyden's canvas. "This way of painting is for the fovea. That is, for that 2% of the retina with which we identify things," he says about how the painter appeals to our visual acuity, the one we would use to search for Waldo in a crowd or a miniaturized baker in a painting by Brueghel the Elder. With a gesture of his hand, he encourages us to get closer to the painting to appreciate the meticulous style of the Flemish master: "He tries to paint reality as it is, to reflect it like a mirror. You can almost take a magnifying glass and see how all the little hairs are painted. Precision gives us a sense of reality; we identify things, yes, but they seem static to us, as if it were a sculpture. In fact, many of these works were done in painting as an alternative to sculptures: the latter were much more expensive."

The intentionality of blur

Francisco Herrera the Younger painted 'The Dream of Saint Joseph' as if it were a blurry photograph: the blurriness of a few points in contrast with the clear vision of others simulates the stimulus received by the retina when we focus on a moving point.

- Why this clash between realism and movement?

- What this painting hides is the conflict between the brain's two systems, the object detection system and the space and movement computation system. The reds of Mary Magdalene and Nicodemus' garments, although they seem brighter, would not stand out from the background if we saw them in black and white. This gives the work a very special vibration without us consciously realizing the reason.

In our next stop, something similar happens, but with a more modern painter trying to capture reality from the opposite technique. We are facing one of Sorolla's most emblematic works. First, he stands far away: "Here are the children on the beach, right?". We nod: we clearly see the kids. Then he takes us just a few centimeters from the canvas: "From this distance, the magnifying glass destroys the painting for you. In reality, there is nothing; the sea, in fact, is just brushstrokes."

His gaze is full of admiration towards Sorolla. He is only trying to show us how the artist's intention has deviated from the foveal style that Van der Weyden applied with a fine brush. Sorolla prefers vitality over realism, and that is why he addresses the other ocular interlocutor: "Here, detail is not important, it's long and applied brushstrokes from a distance, because he is painting for the peripheral retina, with which we normally see the world."

Between the van der Weyden and the sorolla there are about 450 years, but evolutionarily we are the same observer. Therefore, our split perceptual system still plays tricks on us. "The child's leg that we see as brown, if you turn it into black and white, disappears again. The brain's system for computing movement and space gets confused because it sees nothing due to the color contrast, but not light contrast."

This doctor's lessons bridge biology and the joy one feels when contemplating the works. "There is no art without appealing to certain perceptual rules, to that grammar with which the brain processes sensory information. The aesthetic experience would be something like the resonance we experience between the work and ourselves," he explains.

Giráldez quickens the pace to take us to The Dream of Saint Joseph by Francisco Herrera the Younger, where at first sight - the companions gradually begin to understand - we appreciate the intentional blur. Saint Joseph sleeps with his face resting on his left hand, enveloped in a nebula representing the dreamlike result of his imagination.

A combination of size and height signals in 'A Strike of Workers in Vizcaya', by Vicente Cutanda, becomes an effective tool for creating depth. The brain unconsciously detects that bodies, hats, and arms are getting smaller.

- This appeals to our friend, the peripheral retina...

- Exactly, it's like a blurry photograph. That is, this idea that you have to paint in motion so that later you see it naturally.

- Your book says we are never completely still...

- There is nothing that is completely still, right now we have a constant vibration. You look at me while you breathe, and I am moving. So the brain is always immobilizing things.

Room 9 is populated by many other paintings, almost all of them with religious themes. Giráldez invites us to reflect on what we see: "Look at all these virgins, at all these saints: these people were there, they were real in the eyes of those who saw the painting and the faithful even spoke to them. This is what art scholars call presence. It may surprise us, but at that moment it was like their YouTube or TikTok."

Returning to Herrera el Mozo's painting, the neuroscientist explains the reason for the spiral adopted in The Dream of Saint Joseph: "It's like the action lines used in comics to represent movement. This kind of whirlwind is equivalent to when you approach or move away from something, because the retina is a curved plane and the lines are projected concave on it."

All this neuronal activity makes observing a painting not passive. Quite the opposite. "Each act of vision involves receiving information from the retina and, simultaneously, projecting onto it the information already present in the brain," writes Giráldez in the book. And, to make the reflection even more entertaining, he quotes Oliver Sacks: "Each act of perception is in a way an act of creation." Are we then co-authors of Velázquez's paintings? In a sense, yes: Las Meninas are, in their mind, similar to the neighbor's Las Meninas, but not exactly the same.

In another room, the characters of El Greco's Pentecost await us. The neuroscientist that Doménikos Theotokópoulos carried within manifested through the color combinations chosen for the Virgin's and the Apostles' mantles. Giráldez points to the tunics: "There his brush opposes red and green; and there yellow and blue: these are the natural oppositions of our visual system. To compute color in the brain, we make pairs. For example, how much red against how much green. This allows the brain to compute contrast independently of the light that shines."

Color Opposition in El Greco

The use of red-green and blue-yellow as opposing elements is appreciated in El Greco's 'Pentecost', used by him to enhance the prominence of the mantles and the halo of the dove. The physiology of vision allows the master to 'translate' his symbols.

We bid farewell to Pentecost, and by Giráldez's way of speaking, one might say he has saved the best for last: "For me, the great discovery has been Titian. He is somewhat the origin of all this modern painting; of this type of artistic brushstroke, of painting with a stain. He creates a vitality that had not been achieved before. He is painting according to our natural way of seeing, simulating the way of seeing with little detail of the peripheral retina."

The neuroscientist turns towards one of the main galleries of the Prado Museum, where he expects to find The Glory, the painting that the Venetian painted for Charles V. However, due to the live nature of the visit, his attention is immediately captured by a painting by El Greco brought for a temporary exhibition: The Assumption of Mary. "Look at that: you bring someone here from China or from Peru, from wherever, and they will surely be amazed too. This is the half-second impact that art has: you see a lady flying there! To start talking about the assumption, you have to convince people that this woman is floating in the air and that your senses swallow it," improvises our guide.

The flash that Giráldez experienced with the vision of The Assumption may last as long as a blink, but it is a blink that marks everything: "Those 400 milliseconds are what we take to form an image and that first sensation is inherent to art. If you take away that ability to reach the senses, painting becomes a description, it loses vitality. There, in that connection, biology and art touch each other."

To deceive the mind and attract the gaze to where he wanted, El Greco distorted the size relationship between the Virgin's legs and torso. Great masters, like good magicians, perform illusions with their color palette. The same can be said of The Glory: "The characters above [the Father and the Son of the Trinity] and the Virgin are larger than they should be if they were further away. That effect brings the images forward, brings them closer to you, and at the same time, puts them behind the cloud, creating a kind of hollow in the center of the painting."

There is no time for more. A guard arrives: "It's eight o'clock, we're closing." One is left wanting more paintings and more neuroscience. But we must leave now, through the Goya door, to enter the rainy afternoon of Madrid. While we were inside, the drops falling from the sky have painted the landscape gray.