Between 2008 and 2019, José Teruel directed the annotated edition of seven volumes of the complete works of Carmen Martín Gaite (1925-2000), in addition to editing volumes of conferences, stories, poems, and articles for the Siruela publishing house for years. An immersion that could only culminate with the biography of a writer who, as he explains to EL MUNDO, "made literature from life and life from literature. This exhaustive knowledge of her work, from the well-known titles to the scattered and even unpublished ones, through the careful reading of her personal notebooks, agendas, and correspondence, was what drove me to delve into the biological aspect of her work, because in Carmiña both are inseparable".

A philologist by training, honorary professor of Spanish Literature at the Autonomous University of Madrid, and also an expert in the works of Luis Cernuda, Gerardo Diego, and Carmen Laforet, Teruel insists on this bioliterary correspondence. "In her novels, it is easy to notice how beneath the surface of the plots, beneath the fiction's clothing, there always flows the underground river of self-writing, of the biographical. But always subtly, she never signed a strictly autobiographical piece, she was very wary of that genre, so popular today," clarifies the professor. "However, the frame of reference of her literary world was nourished by a category called experience."

Carmen Martín Gaite. A Biography, the work that won the Comillas Prize 2025 awarded by the Tusquets publishing house, is a meticulous, engaging, and revealing reconstruction of the life of the author from Salamanca, addressing chronologically: family background; her education in Salamanca; her friendship with Ignacio Aldecoa and her arrival in Madrid and into the literary group of the 50s generation; her courtship, marriage, and subsequent separation from Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio, her relationship with her daughter Marta and her tragic death, and that last decade of successes and recognitions.

In those origins, seasoned with growing up in a bleak post-war period, Teruel finds many of the keys to the writer's peculiar perspective, in which memory and the need to evoke it to understand and understand ourselves play a key role. "Martín Gaite always showed a strong sense of filiation: 'My parents were in the background of everything I did, even if I didn't see them', she once said, and she always defined herself as a provincial lady, the daughter of a notary," he explains.

In that sense, beyond an elitist education, the writer enjoyed a cultured father, a great reader with an impressive library, and a very imaginative, very intuitive mother who liked adventure novels and romance novels. "These two libraries make a good stew in the case of the multifaceted Carmiña: Clarín, Galdós, Unamuno, and Baroja on the father's side and The Three Musketeers and the sentimental novels of the time on the mother's side".

Regarding the morality and daily life of the post-war period, very present in works like Among the Suitors, The Back Room, or Amorous Uses of Post-war Spain, the biographer highlights that despite her favorable family and economic circumstances, "the atmosphere was hostile, and the most frequent words were fear and cold. As she wrote, the restriction not only affected ration cards but also behaviors and affections, especially relationships between men and women," emphasizes Teruel. "Not just sex itself, a word that hardly existed, what she noted was that what was forbidden was friendship and sincerity between men and women. As she always said, censorship affected her more in life than in literature."

"She was an inner rebel with a life marked by tragedy"

Perhaps that is why in her books, especially in the early ones, there is a compassionate look towards women and also hints of a pioneering feminism based on action. "Martín Gaite, who was a very intelligent woman, started from obedience to disobey. In this, she was very similar to Saint Teresa. Her rebellion was always deeply rooted but also very internal. She was an inner rebel with a tragic life," reflects Teruel, adding that her essays on amorous uses in the 18th century and post-war period arose "because she was concerned about the fate of women, always educated in the push and pull of asserting oneself and pleasing as a commodity geared towards marriage."

However, Teruel recalls that not everything was idyllic, far from it. Beyond the death of her son Miguel, who died of meningitis in 1954, at only seven months old, "starting in 1960, the most critical decade of her life, Martín Gaite began to experience her husband's oddities, his maladjustment, and even his self-destructive tendencies. From then on, she did not allow Rafael to read anything she wrote because she knew it could influence him negatively, that his criticisms could be very negative. The literary admiration persisted, more on her part, but the relationship was broken."

Also in that fateful decade of the 60s, the writer suffered the deaths of her two great friends Ignacio Aldecoa and Luis Martín-Santos, "two great writers who did recognize her, perhaps the most sensitive to her work and those who understood her best, as evidenced by the dedication that Martín-Santos wrote in 1963 in his copy of Time of Silence," highlights the biographer, recalling that Martín Gaite wrote several articles, profiles, and forewords about her generation. "Not only was she a participant in this group of writers from the 50s, but she was also a legatee, she bequeathed to those of us who came after stories of that generation. She wrote about everyone, and except for these two, they were not very generous with her."

"Literature was for her a defense against life's offenses"

In this sense, Teruel elaborates on the idea of literature that the writer matured. "Literature was for her a defense against life's offenses. She understood it as an escape from lack of communication, as a refuge, and also as a beacon. For her, it was the possibility of getting to know ourselves better, of asking unanswered questions, of questioning things," summarizes the biographer. Another aspect he highlights, which generates empathy with the reader, is the idea that "learning never ends. She identified the writer's luck with that of the bullfighter because she said that writing is a craft whose learning is only validated by practice. In fact, she always felt somewhat drained when she finished a novel, with the terrible feeling that she wouldn't be able to write another. In other words, she always preferred to die learning than to die knowing."

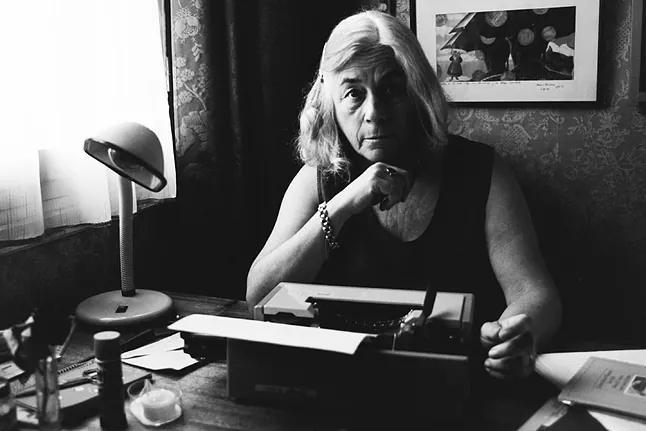

Paradoxically, it was in the late 80s and 90s when the public Martín Gaite took shape, the smiling writer, armed with a smoking cigarette and a tilted beret, who began to reap recognitions and meet readers. "Her radical freedom is evident in those fairy tales like The Devil's Cake, The Castle of the Three Walls, Little Red Riding Hood, or The Snow Queen. It was a very personal and offbeat outlet, something absolutely unpredictable within her generation. It was like saying: I do what I want and I don't ask anyone's permission, and if it amuses me to write fairy tales as emotional support, I do it," concludes Teruel.

"She narrated the life of her audience from home, that place where History is truly cooked".