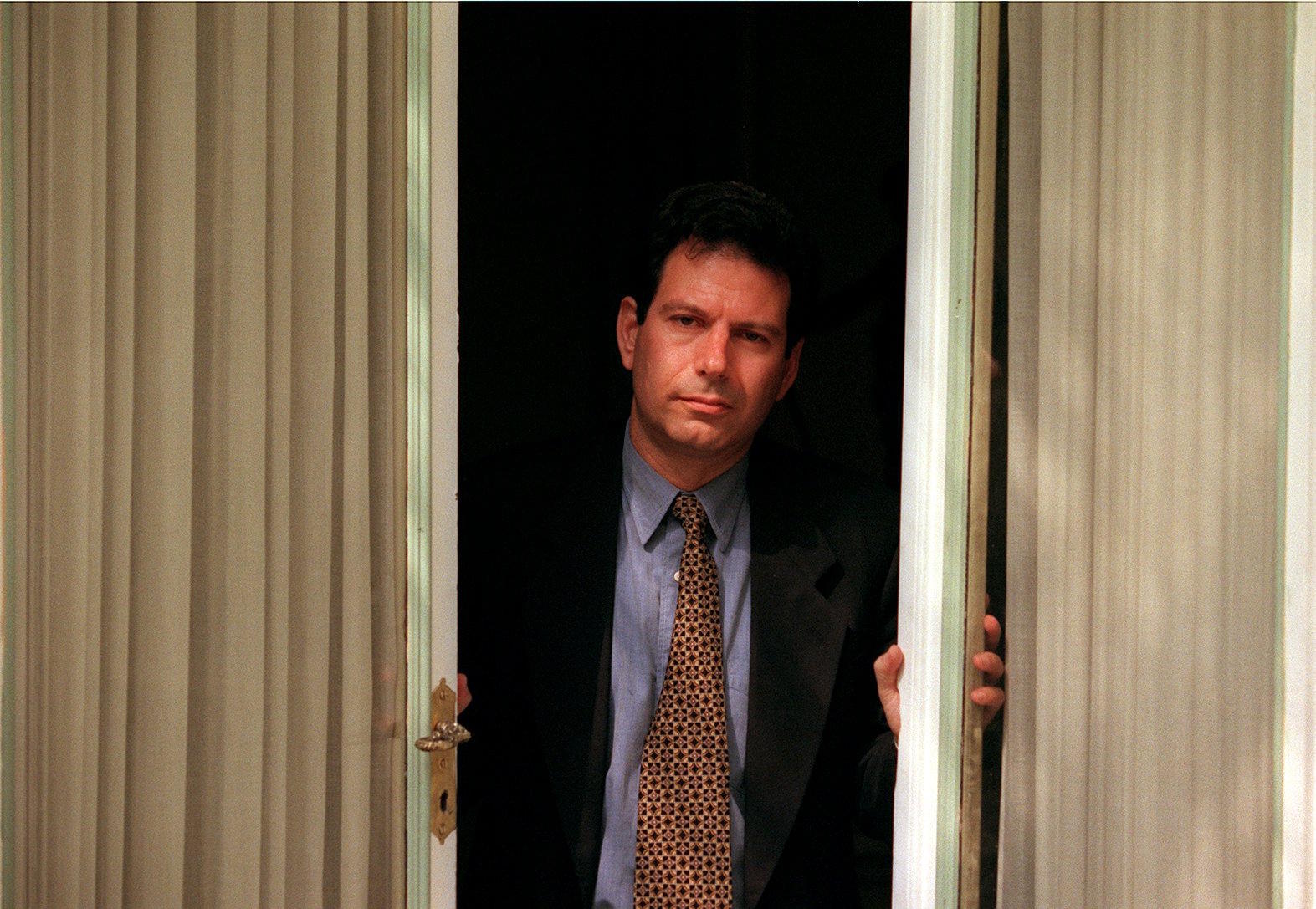

s cliché as it may sound, lessons from the past often contain useful and decipherable warnings, just pay attention to the signs. This is the opinion of the controversial journalist, political analyst, and essayist Robert D. Kaplan (New York, 1952) when comparing the current global situation with the Weimar Republic, the ephemeral and fragile state that preceded the Third Reich, which has been a parable for decades of a society unaware of its own need for order and state power and therefore doomed to be punished by state power in its most vengeful and cruel form.

The comparison of the current United States with Weimar has been constant since the second victory of Donald Trump, but in his new essay, The Wasteland (RBA) - where the title of T. S. Eliot's poem is also a metaphor and one of the many literary references - the American thinker, who stated not long ago that "if Donald Trump is reelected, the liberal world order may be in serious danger," writes: "the revelers of Weimar, in love with anarchy and end-of-the-world parties, had no idea what awaited them. The more abject the disorder, the more extreme the tyranny that often follows."

"The years from 1919 to 1933 were a time of permanent crisis in Germany. Weimar was the opposite of an authoritarian state; it was a chaotic state, and that is how our world is today, a kind of global Weimar," he argues from his home office in New York, in a teleconferencing conversation with La Lectura, a writer for The Atlantic Monthly and a regular contributor to The Washington Post, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal, among other media outlets. "And it is global because, as I argue in the book, technology has reduced geography so that we are closer than ever. We do not have a world government, but we do have a glocal system of political-economic interrelations in which events in Asia, the Middle East, Europe, or North and South America affect each other as never before," he points out, explaining one of the key points of the book.

Kaplan's thesis, one of the most influential thinkers in the US - and, for some, more pessimistic or more bellicose, opinions vary - for a quarter of a century, is based on the idea that we are entering a new era of global instability. The world is facing an era of wars, climate change, rivalry among great powers for resources, and unprecedented technological advances that can undermine the individualism he considers key to the success of Western democracies. "The comparison should not be taken literally, of course," he clarifies with a smile. "The Weimar Republic ended up leading to Hitler, but our world today will be different; it will not end with a totalitarian leader. The world is still too big and diverse for that to happen. However, the example serves me to criticize certain worrying trends."

The first of these, controversial in today's world of well-thinking politics and somewhat naive, is the idea that the order that the West has enjoyed since the end of World War II is infinite and unchangeable. On the contrary, Kaplan believes, citing the reflections of a Winston Churchill, that when governing a state or society, order must take precedence over freedom. "I understand that it may not be pleasant to hear, but history shows us that without order, there is no freedom for anyone," he asserts firmly. "This was something that the founders of the United States deeply considered. Every state needs political order because the opposite of order is anarchy, chaos. Therefore, he emphasizes, order comes before freedom. "Without an appearance of order, people cannot go about their daily lives or do anything, as they always run the risk of being attacked, either physically or by a collapse of the social system. It may seem obvious, but I believe that in the West, order is taken for granted, and it should not be because it was not always there, and in many parts of the world, there is still nothing similar," he evaluates.

But as he has been doing for years in insightful and bold essays like his seminal The Revenge of Geography, The Return of Marco Polo's World, and Adriatic: Geopolitical Keys of Europe's Past and Future, Kaplan does not limit his analysis to mere theoretical approaches. In The Wasteland, the thinker devotes extensive pages to discussing the different but undeniable decline affecting the three major global powers today, the United States, China, and Russia. "The three countries are undergoing significant changes, but all are of different magnitudes and are subject, as is logical in a global world, to the situation experienced by the other competitors," he explains.

"Without order, there can be no freedom. The way democracy is most successful is by not having too much of it,"

He details: "The United States has a comparative advantage because its decline is slower than that of the other two. The decline of my country is happening in the democratic sphere because the political center has disappeared. There is no longer a center or center-left Democratic Party and a center-right Republican Party; now there is a progressive far-left Democratic Party and a populist far-right Republican Party," he categorically opines.

This absence of a political center, which he relates to the rise of technology, causes, as the analyst reasons, "a lack of overlap of political ideals or plans, meaning that each election is a leap, a battle of existential consequences through which tyranny of the majority can be achieved, where 52% tyrannizes the other 48%," he laments. However, he predicts even worse scenarios for China, a country from which, he asserts, "hundreds of billions of dollars are fleeing after several decades of surprising growth in all areas. This is because, in his view, "China is no longer a moderate, risk-averse, collegial authoritarian system; it is largely a Leninist totalitarian autocracy, especially because of its leader Xi Jinping."

But before returning to the Asian giant, to whose ambition to create a massive economic alliance in Eurasia under Beijing's control he dedicated the aforementioned The Return of Marco Polo's World, Kaplan stops at Russia, the country undergoing "the most dramatic fall." According to the thinker, "since the Ukraine war began three years ago, Russia is losing its ability to influence events and decisions in the Caucasus, Central Asia, Siberia, and the Far East," traditional areas of Russian and Soviet Empire influence and control. Its power is silently crumbling due to financial pressures, internal population pressures, and the disastrous decision-making in the war in Ukraine," he harshly summarizes.