Any comparison in certain cases is inappropriate. Especially when it comes to comparing massacres. But there we are. Or there is the Berlinale. Last year, the speech at the award ceremony for the Palestinian-Israeli documentary nominated for an Oscar No other land, where the word apartheid alternated with genocide to describe the situation in both the West Bank and Gaza, led a large part of the German political class, as well as the Government of Israel, to demand the total absence of reference at the closing gala to the Israeli hostages on October 7, 2023. This year, perhaps in an attempt to atone not so much for a sin as for a guilt complex in advance, the Berlinale has gone all out.

In addition to the full screening of Claude Lanzmann's monumental work Shoah on its 40th anniversary, they have added the world premiere of Guillaume Ribot's documentary Je n'avais que le néant (I only had nothing), which recaps the long process of making the film while rescuing unpublished material. Also, and finally, the victims of the Nir Oz kibbutz take center stage in A letter to David, by Tom Shoval, through the story of two twin brothers who, a decade earlier, became unlikely movie stars. Additionally, beyond an inconsequential parcour documentary, we know nothing more about Palestinian cinema in this edition.

If we want to talk about cinema before politics (if it is possible to separate them), the first thing to note is the relevance and brilliance, more of the former than the latter, of the two premieres. Je n'avais que le néant reveals the behind-the-scenes of a project that its director took over 12 years to film and edit. In essence, the unseen footage now revealed adds little to the original content of over 9 hours, but, and this is important, it returns Shoah, now rightfully elevated to the status of a myth, to the deeply human mud from which it emerged. Our mud, the mud of all. "Claude, if you licked my heart, you would be poisoned," says one of the survivors of the Warsaw Ghetto in Israel, and it is for that sentence that shakes the world that the film remains safe. The film delves into the behind-the-scenes, the doubts, and even the impossible adventures (everything that happened when they insisted on secretly filming a member of the Einsatzgruppen) of the filming. And it does so not so much with the intention of a notary, but with something as exciting as pure emotion. Suddenly, Shoah, the film that looked "at the black sun of the Holocaust," takes on the character of the unstable, the fragile, the, as has been said, human. How many times was a work almost lost without which it would now be impossible to understand even cinema itself!

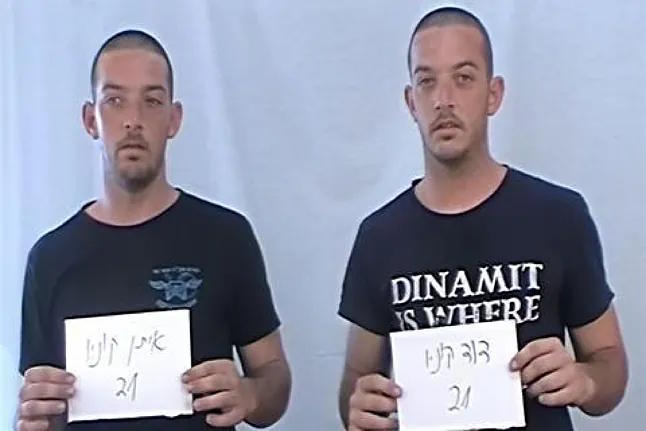

The case of A letter to David is so particular that if it were fiction, it would be accused of being simply implausible. Twelve years ago, the film Youth by director Tom Shoval was presented in Berlin. It starred two twin brothers, Eitan and David Cunio. It tells the story of the kidnapping of a young woman. Time passes, and on October 7, a decade after the Cunio brothers' debut as actors, one of them, David, is himself kidnapped along with his younger brother Ariel. The documentary, produced by Nancy Spielberg (sister of Steven), mixes real-time destruction and anxious waiting (they are still kidnapped) with archive footage of the family and scenes from both the casting and the movie that the two brothers starred in, now separated by an abyss. A strange sense of unreality pervades every second of a film that moves with equal ease and pain through fantasy, horror, and simple fear. There is also room for hope, but less.

In other words, there is little or nothing to object to in the selection of each of the works from the point of view of their timeliness, quality, and depth. The only objectionable thing, in fact, is their loneliness. It is still incomprehensible that there is nothing in this edition that reflects Palestinian suffering. That is, if the festival acknowledges as a mistake, as it seems to have done, leaving out the Israeli drama as it did last year. This year, the same mistake is made. But in reverse.

The new festival director, Tricia Tuttle, warned at the start of the event that freedom of expression would be respected, that everyone could display the symbols they wanted, but, of course, within the law. That is, just as German law prohibits swastikas as symbols of hate, the State of Berlin does not allow the expression "From the river to the sea" for inciting hatred (assuming that hatreds can be distinguished from each other), to the extermination of the State of Israel. Far from having achieved any peace, the Berlinale already has its first conflict in the courts. Last Saturday, Hong Kong filmmaker Jun Li read out words from his lead actor, the Iranian Erfran Shekarriz, absent in the German capital for all the reasons explained earlier, during the presentation of the film Queerpanorama. And what was on his phone? Indeed: "From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free." Who should the police pursue? The attentive reader or the absent author? And so on.

Any comparison is inappropriate, but it seems clear that the mistakes of the past insist on being as large as those of the present.