Human nature remains the same regardless of the era. Centuries ago, there were swindlers, fraudsters, and scammers just like there are today. A team of researchers has uncovered a case of tax fraud involving slaves in the Roman Empire, specifically in the provinces of Judea and Arabia, through the analysis of a new papyrus, as reported by Servimedia.

The details are outlined in a study conducted by researchers from the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the University of Vienna (Austria), and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Israel), published in the international academic journal 'Tyche'.

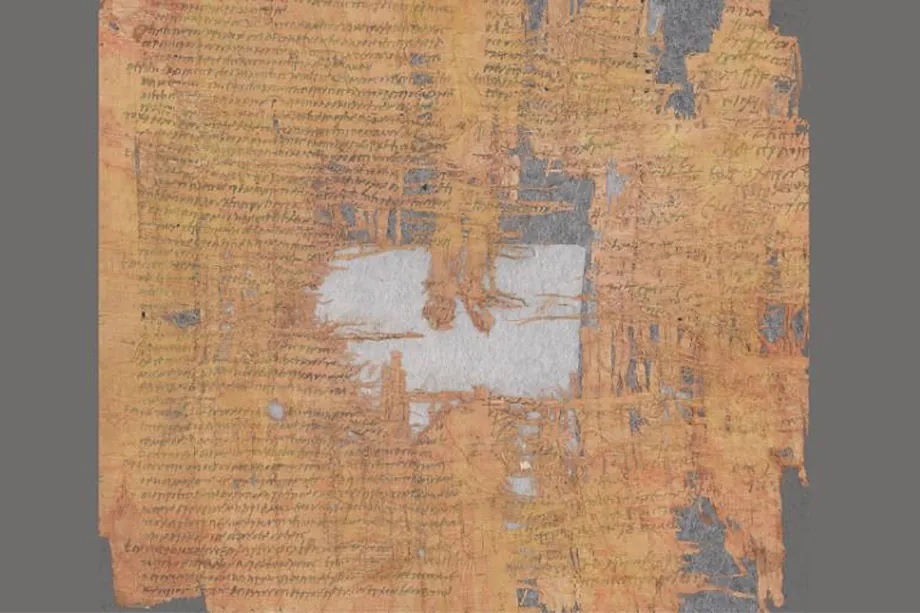

The papyrus, belonging to the collections of the Israel Antiquities Authority, provides a rare insight into Roman legal procedures and life in the Roman Near East.

The research team reveals how the Roman Empire dealt with financial crimes (specifically tax fraud involving slaves) in Judea and Arabia.

The new papyrus offers a surprisingly direct view of Roman jurisdiction and legal practice, as well as new and important information about a turbulent era shaken by two massive Jewish revolts against Roman rule.

The papyrus is the longest ever found in the Judean desert, with over 133 lines of text. Initially misclassified as Nabatean, it went unnoticed for decades until it was rediscovered in 2014 by Hannah Cotton Paltiel from the Hebrew University.

"I volunteered to organize documentary papyri in the parchment laboratory of the Israel Antiquities Authority. When I saw it marked as 'Nabatean,' I exclaimed, 'To me, it's Greek!'" recalls Cotton Paltiel.

In recognition of her discovery, the papyrus has been named 'P. Cotton,' following papyrological conventions.

Cotton Paltiel, recognizing the extraordinary length of the document, its complex style, and its potential links to Roman judicial proceedings, assembled an international team to decipher it.

The team, including Anna Dolganov from the Austrian Academy of Sciences; Fritz Mitthof from the University of Vienna, and Avner Ecker from the Hebrew University, determined that it was notes from prosecutors for a trial before Roman officials on the eve of the Bar Kokhba revolt (132-136 AD), including a hastily written transcript of the actual court hearing.

The language is vibrant and direct, with one prosecutor advising another on the strength of various evidence and devising strategies to anticipate objections. "This papyrus is extraordinary because it provides a direct view of trial preparations in this part of the Roman Empire," notes Dolganov. Ecker adds: "This is the best-documented Roman judicial case in Judea, apart from the trial of Jesus."

The papyrus details a case of forgery, tax evasion, fraudulent sale, and manumission of slaves in the Roman provinces of Judea and Arabia, corresponding approximately to present-day Israel and Jordan.

The main accused, Gadalias and Saulos, are charged with corruption. The former, the son of a notary and possibly a Roman citizen, had a criminal record related to violence, extortion, forgery, and incitement to rebellion. The latter was his accomplice and orchestrated the fictitious sale and manumission of slaves without paying the corresponding Roman taxes.

To conceal their activities, the accused falsified documents. "Forgery and tax fraud carried severe penalties under Roman law, including forced labor or even the death penalty," points out Dolganov.

This criminal case unfolded between two major Jewish uprisings against Roman rule: the Jewish diaspora revolt (115-117 AD) and the Bar Kokhba revolt (132-136 AD).

The text implicates Gadalias and Saulos in rebellious activities during Emperor Adriano's visit to the region (129-130 AD) and names Tineius Rufus, the governor of Judea when the Bar Kokhba revolt began.

Following previous disturbances, the Roman authorities likely viewed the accused with suspicion, linking their crimes to broader conspiracies against the Empire.

"It remains to be seen if they were truly involved in the rebellion, but the implication speaks to the charged atmosphere of the time," notes Dolganov.

As Ecker points out, the nature of the crime raises questions, as "freeing slaves does not seem to be a profitable business model."

The origin of the enslaved individuals is unclear, but the case may have been related to illicit human trafficking or the Jewish biblical duty to redeem enslaved Jews.

The papyrus provides new insights into Roman law in the Greek-speaking Eastern Empire, referencing the round of trials by the Judean governor and mandatory jury service.

"This document demonstrates that fundamental Roman institutions documented in Egypt were also implemented throughout the Empire," Mitthof points out.

The papyrus also showcases the Roman State's ability to regulate private transactions even in remote regions. Likely originating in a hidden cave in the Judean desert during the Bar Kokhba revolt, its careful preservation remains a mystery, and the trial's outcome may have been disrupted by the rebellion.