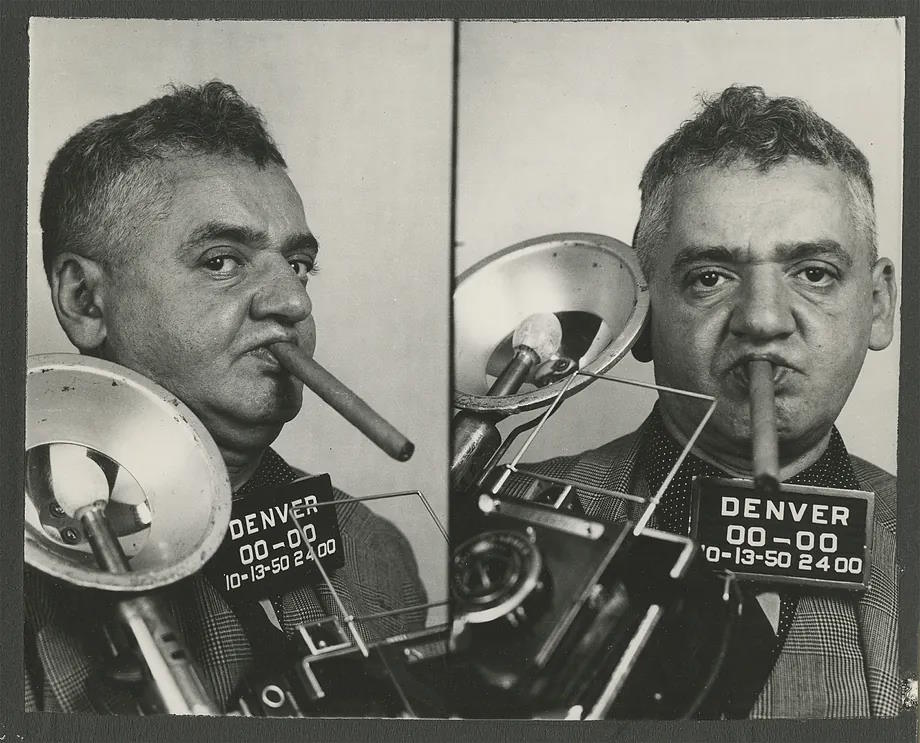

"My name is Weegee. I am the best photographer in the world." He was convinced that he should present himself in a grand way, but in this self-assurance, there were two suspicions: perhaps it wasn't all that true, and his name wasn't even Weegee. His name was actually this: Arthur H. Fellig. And not even that is accurate because his parents registered him as Usher Fellig. He was born in present-day Ukraine in 1899. He arrived in New York in 1909. In his adolescence, he acquired his first camera and never accepted any other mission than to capture the strangest. The most sordid. That's how he made a name for himself among Manhattan photographers. And he indeed became the fastest. Weegee is the pseudonym he gave himself, a phonetic interpretation of the word ouija. Because Weegee was, like spirits, everywhere.

He instinctively learned to be a street photographer, but from the darkest corners, the worst territories. And from the most intense events: crimes, suicides, accidents, scenes of brawls... No one was faster than Weegee, able to smell the blood before it spilled, willing to place the camera's flash closer to the face of the deceased, to the hole where the blood was draining.

His images were brutal, of a raw realism, never softening the scene. He saved the sweetness for the other side of his work: portraits of New York's high society in the 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s, as Weegee lived until 1968.

But it is to his raw work that the Mapfre Foundation in Madrid dedicates the exhibition "Weegee, autopsy of the spectacle." Open from September 19 to January 5, curated by Clément Chéroux, director of the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson.

In the concentric circles of the police, pimps, gamblers, ladies and gentlemen of the night, drug dealers, and ambulance drivers, Weegee was a highly respected professional. In 1938, he obtained the only private license in New York to have a portable shortwave radio in his car connected to the police frequency. In the trunk of his car, he set up a darkroom to develop photographs before anyone else and distribute them to newsrooms. He lived in his two-seater car and arranged everything he needed for major crime scenes: rubber boots, coat, salami, many socks, a typewriter, dozens of flashbulbs...

Sleeping at the circus, Madison Square Garden, New York, June 28, 1943Weegee

He worked at night, of course. He arrived at the crime scene before anyone else. When the police arrived, Weegee had already smoked half a cigarette. Weegee's photographs are the best witness to the marginal reality of New York. But also to the nightlife and golden frivolity at the parties of the well-off families. Witness to the filth and the spectacle. And he didn't need any decompression between one scene and another. Weegee's eye was trained not to blink out of laziness or astonishment.

The Mapfre exhibition also includes some pieces of his other photographic preference: the rich and their customs. He was a reporter. Precisely a brutal reporter. Fast as blood. Distrustful. Invisible when necessary. His images appeared in the Herald Tribune, the Daily News, the Washington Post, or The Sun. He had no rival in his jurisdiction. Where Weegee was, something always happened that he captured first, revealed first, and released first. And it was always extraordinary.