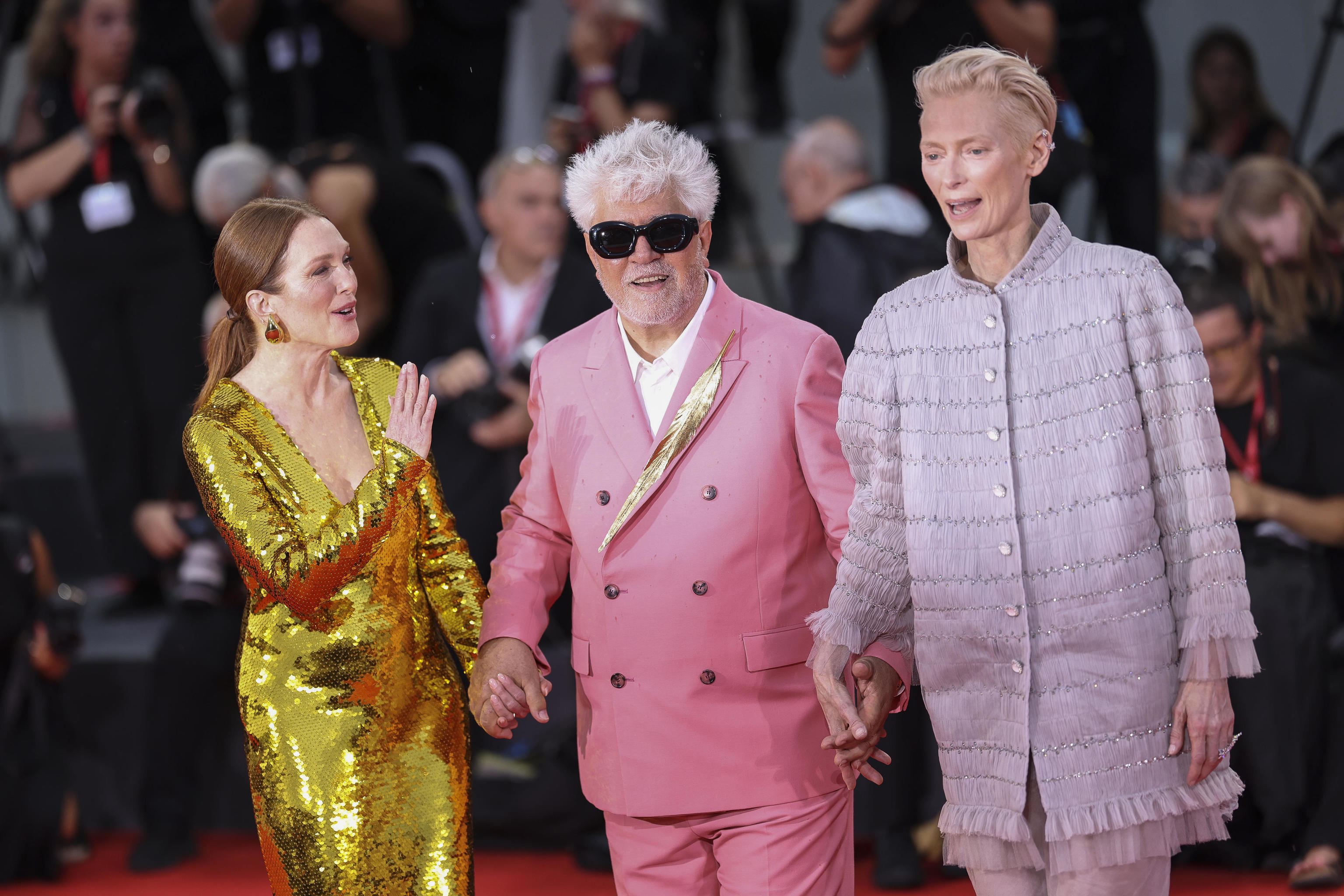

Cinema is an art of contradictions. The main discovery of sound cinema was, who would have imagined, the expressive power of silence. When tired of the competition from the gray and tiny television, the major studios desperately expanded the screen to infinity, what filmmakers discovered was that no landscape can be compared in depth, abyssal geographical accidents, and torrents of pure pain (and pleasure too) with the human face. The Room Next Door, the latest film by Pedro Almodóvar (the 23rd in his filmography or the first shot in English, as you prefer), celebrates each of the paradoxes that inhabit cinema (or a good part of them) and does so with a contained precision on the verge of enthusiasm that overflowed at the end of the screening, when the audience at the Venice Film Festival remained standing, applauding for 17 minutes in a historic ovation.

It is a film about life from the clarity of death; it is sober to the point of agony, but flooded with vivid colors; it is a melodrama by definition exuberant and yet, it all fits into the quiet music of mourning; it promises a great love story and, no surprises here, there is the purest passion transmuted into the steel thread that binds two friends on the brink of all precipices. But above all, Almodóvar's adaptation of Sigrid Nunez's novel What Are You Going Through is nothing more than a map, the map of the territory of the human face. And it is done with an admirable yet enigmatic precision.

The faces of Tilda Swinton and Julianne Moore map out with such clarity the very territory of emotions that they turn the screen into a mirror where we look at ourselves and sink. And they themselves, the actresses, end up being real characters of their fiction. Actresses of themselves, representations of an atavistic desperation that appeals to us all. The repeated reference to The Dead, John Huston's adaptation of Dubliners by James Joyce; as well as the veiled appearance of Letter from an Unknown Woman, by Max Ophüls based on the story by Stefan Zweig, are the clues that The Room Next Door... leaves for each one's memory to replicate their own ghosts and fears.

It tells the story of two friends who reunite after a long time. The first (Moore) is a novelist and the second (Swinton) is a war reporter. One has just published a book about death that she does not understand, and the other, due to cancer, is simply dying. What follows is a journey of recognition, salvation, guilt, and forgiveness. But also of freedom in choosing how to die.

The director focuses, as mentioned, on faces in close-up or extreme close-up. And there he stays to live. And to die. The entire film is offered as a study and reflection on the power of gaze and word.The Room Next Door is entirely built on a text that the protagonists recite close to each other and, at the same time, in a dreamlike state in their solitude. Almost in a trance. The words become not so much images as perfectly filmable (and even inflammable) imaginary material. Silence matters, the other side of what is said, the shadows behind a space always illuminated from above. The monologues so common in the director's cinema are now spaces for friendship and solace. And all this, while, as in the best cinema of the melodrama master Douglas Sirk, the world is presented through window and door frames that delimit screens, screens within the cinema screen itself; images reflected in images. Once again, few filmmakers are as meticulous as Almodóvar in drawing the labyrinths of representation where reality intertwines with fable, and vice versa.

The result is a thematic continuation of Pain and Glory, but from a more serious, wounded, and profound place (how much The Room Next Door reminds us of Talk to Her and how much Tilda and Moore make us think of the imperial Marisa Paredes). Now, unlike in his previous film, what is relevant is not so much the past life projected in guilt (which is also there, as an abandoned daughter appears) but that immediate and blind future that stops everything, nullifies everything, and, in the same way, justifies everything and gives meaning to everything. It could even be said that the backward jumps in the form of flashbacks are elements that do not quite fit into the icy and perfect seriousness of the whole. The references to the Vietnam War are rather touristic and quite unnecessary. If the stories within stories in the director's cinema have always served the purpose of expanding what we could call the narrative life cycle, in The Room Next Door they seem to be mere mistakes that interrupt the quiet and profound pulse of everything.

Nevertheless, what remains is a symphony of two faces turned into such a perfect map that it ends up being the territory itself, the territory of the soul. There is no difference between the characters and the actresses, cinema and reality, death and life... the map and the territory. Borges wondered why it unsettles us that a map is included in a map, and the thousand and one nights in the book of The Arabian Nights, and Don Quixote is a reader of Don Quixote, and Hamlet, a spectator of Hamlet. And he answered: "...if the characters of a fiction can be readers or spectators, we, their readers or spectators, can be fictitious." Undoubtedly, a film, The Room Next Door, for the emotion.