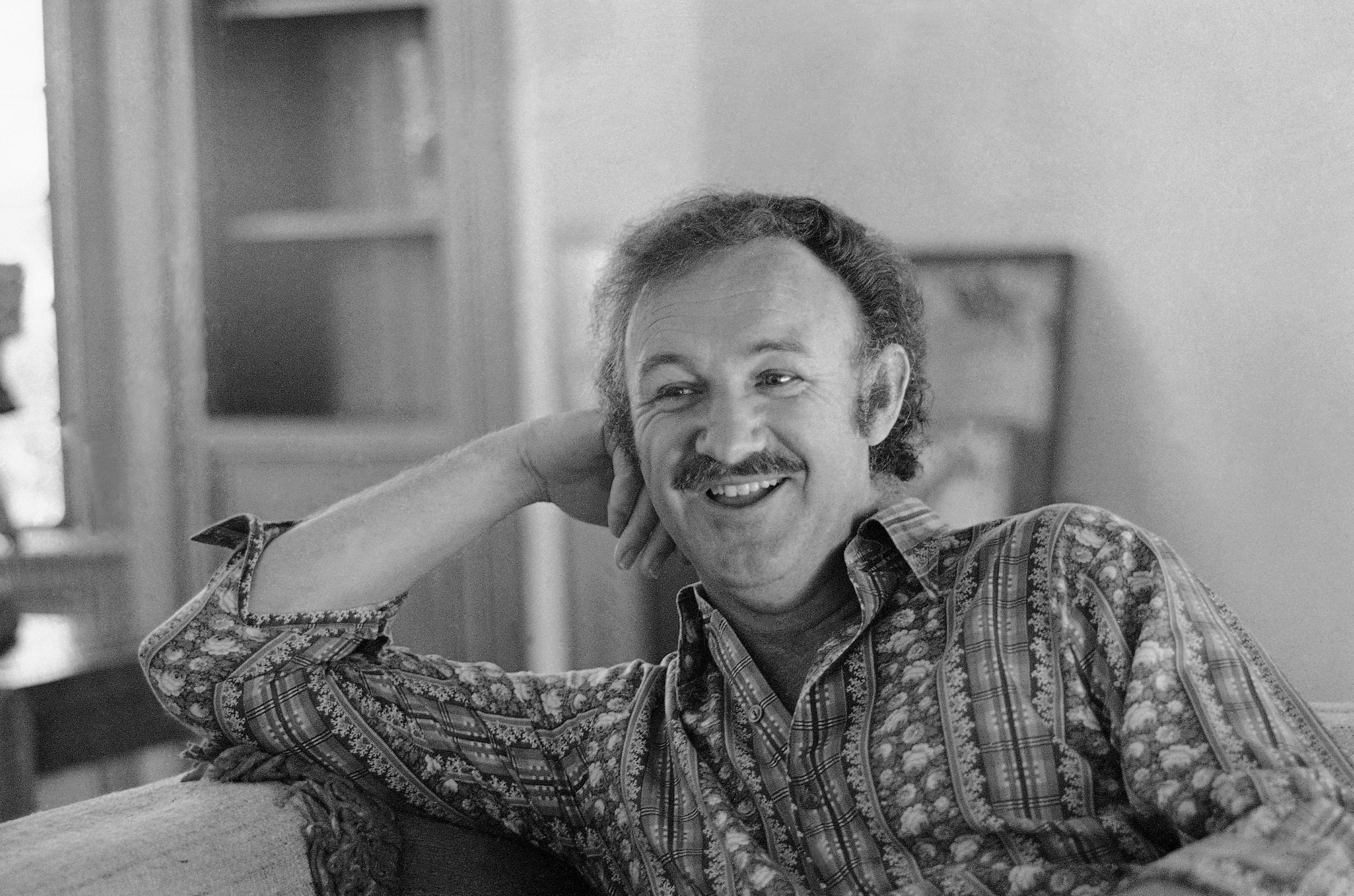

"He tried. I think that phrase sums up my life." In one of the last interviews he gave, when the journalist asked him to summarize his career, he, in a laconic and very Hackman-esque way, left it at that: "He tried." Gene Hackman, in fact, spent a whole life trying everything, trying to be anyone in general, which is a way of being each and every one of us, which is the only possible way to be an actor. Due to his always explosive style of acting, his uncommon physical appearance, his beautiful and electrifying ugliness, Gene Hackman was always an actor (later, towards the end of his life, also a writer) far from any kind of definition, schematism, or categorization. He was able to merge with each of his characters, always being different, without ever giving up on being himself, always identical to himself. Until the end of a life that lasted 95 years.

When the pattern of the classic leading man collapsed and the screen was filled with individuals as short as Al Pacino, as sinister as De Niro, or as versatile and chameleon-like as Dustin Hoffman, he, the star of a handful of masterpieces like The French Connection, The Conversation, Scarecrow, Night Moves, The Poseidon Adventure, Young Frankenstein, A Bridge Too Far, all the Superman movies we love, Another Woman or, of course, and above all else, Unforgiven; he, Eugene Allen Hackman, was everything, tried everything, was everyone.

Choosing a single role (or ten or 20) in a career that spanned 40 years until his retirement in 2004 seems practically impossible. Although one tries hard. With over 80 works, he left his mark on all of them, always different, always the same. His first eternal work came from the hand of William Friedkin when he offered him to be Jimmy Popeye Doyle in The French Connection. There, in a film shot in five weeks in the winter of 1970 and against all common sense precautions, Hackman offered himself unambiguously on the brink of all suicides. The desperation of a man condemned to death (that's what it's about) looks perfect in the impulsive and furious gesture of the protagonist turned into a Beckett character with a gun in hand. Or in the ankle. Nothing makes sense in him, victim and executioner at the same time, except the ruthless constancy of the basic: the primary suffocation of the simplest of pursuits. You run, yes, but where to.

Born in 1930, he joined the Navy in the late 1940s and only decided to study acting in the late 50s. He was almost 30 years old then. Hackman became friends with Dustin Hoffman at the Pasadena Playhouse, and both were unanimously voted as the best promises of failure. The title given was "the least likely to succeed." And so it went until he made his film debut alongside Warren Beatty in Lilith in 1964, followed by playing Buck Barrow in Bonnie and Clyde, directed by Arthur Penn, a film in which his colleague Beatty was the producer. It was his first Oscar nomination. But not only that, Hackman didn't know it yet, but he had just founded an entire universe. The New Hollywood, of which he would be an essential figure, had just been born. The best attempt, undoubtedly.

Then came Jimmy Popeye Doyle and with it his first Oscar in 1971.

What followed was a glorious decade. His. The 70s. The one that would define contemporary cinema up to this day. Hackman was the priest who sacrificed himself for everyone in the best disaster movies. The Poseidon Adventure (Ronald Neame, 1972) marked his baptism in the most popular cinema and his consecration as the character who always had to be respected. And loved. You were either on Hackman's team or you were out. His role alongside Al Pacino in Scarecrow (Jerry Schatzberg, 1973) as a vagabond not only exposed the famous American dream but did so with grace. Just as hilariously funny was his collaboration in Young Frankenstein (Mel Brooks, 1974). The toughest and most corrupt of cops could also be the most insane and absurd of mad doctors.

That same year, the glorious 74, Hackman brought to life Harry Caul, the detective who simply listens and plays the saxophone in The Conversation, the film by Francis Ford Coppola that won the Palme d'Or and redefined the parameters of what can and cannot be told, what is seen and what is on the screen. The masterful film that unfolds entirely off-screen already and forever placed him in the Olympus; a place reserved for those who try their best (and those who fail the best) from where he delivered only a year later two more eternal films: Night Moves, by Arthur Penn, and Bite the Bullet, by Richard Brooks. The thriller and the western were experiencing their particular revolutions in Hackman's chiseled face. Along the way, he made some of those gestures that further magnify his figure: he was the man who said no to Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and Raiders of the Lost Ark.

What followed is incomparable. Or maybe it is, depending on how you look at it. Waiting for his resurrection in Unforgiven, Clint Eastwood's work that earned him his second Oscar in 1992, the actor went through the 80s in top form and with a strong desire to blow everything up. Literally. That and nothing else was always the intention of his Lex Luthor. His involvement in Richard Donner's Superman and subsequent films not only made Marlon Brando himself look ridiculous but also made us not care at all for the first time that the world would end forever. We were with him. And it would continue to be so when he insisted on Hoosiers (David Anspaugh, 1986) that we win the basketball title that eluded us and it would be so again in his unique fight against racism in Mississippi Burning.

There, in Alan Parker's 1988 film, the rough and always effective (as well as efficient) director let the camera focus on Hackman's rough, perhaps brutal manners. And that's where the identification with the audience emerged, in the man who, to achieve his goals (no matter how good and holy they may be), obeys the viewer's always base instincts. Again, always with him, always by his side, no matter how wild and unfortunate his choice may be. And so it went until Unforgiven.The Eastwood-Hackman duel is more than just the encounter of two legendary actors, it is a meeting in the hell of two gods. Exactly.

What follows until the end and before he, due to stress (as the doctor told him after carefully examining his heart), turned into a writer, is the dignified walk of a myth through his own well-deserved mythology. He tried, he says, and in what a way. The Firm, Crimson Tide, Absolute Power or Runaway Jury are examples of the most Hackman-like Hackman. But how can we forget his delirious and brilliant role in The Royal Tenenbaums, by Wes Anderson? It wasn't his last attempt, but it was one of his best last attempts. "He tried. I think that phrase sums up my life," he said. RIP